Thanks to Charlie Horse 47 and Killdumpster for their sponsorship of this post, via the magic of Patreon.

***

If there's one thing visitors to this site can take for granted, it's that it will never be anything but topical.

And so it is that, this Easter Sunday, it can be found reviewing that most Easterly of comics.

Shazam #5.

OK, I admit it. It has nothing to do with Easter. But, who knows? Maybe we can find a little of that Easter magic contained somewhere within its pages.

I first acquired this comic in the early 1970s in a shop just beyond the city centre, before being dragged into a small butcher's shop where the elderly customers were complaining they'd never get used to this new money the government had brought in which involved having to know the ten times table, as opposed to the twelve times table.

How appropriate, then, that also concerned with money is small-time crook Slip Kelly who, in our first tale of the issue, encounters no less a dignitary than a visiting leprechaun.

Grabbing it, he claims his one wish and is granted the power of invisibility.

With that, he robs the local bank, simply by walking out of it with a large pile of banknotes in his hands.

Fortunately for the bank - but not for Slip - clean-cut child Billy Batson just happens to be there and, quickly transforming himself into the Original Captain Marvel, sets about tackling the situation.

However, the leprechaun reveals that Slip can only be restored to visibility by cancelling his own wish.

And Original Cap knows just how to make him do it.

He drops Slip from a great height, knowing that because he can't see him to rescue him, he has no way to prevent the crook from being splattered upon impact with the ground. Thus it is that Slip can only survive if he re-grabs the leprechaun and demands it make him visible again.

I'm not sure if I should point out that, if Slip hadn't managed to catch the leprechaun on the way down, he'd now be a huge red mess on the road and Original Cap would be facing a murder charge, lending the whole plan a far darker edge than it's, presumably, meant to have.

My main takeaway from this, the issue's first tale, is that CC Beck's art has a cartoony simplicity to it that's totally at odds with how super-hero comics were drawn at the time but has an easy-on-the-eyes charisma you can't help but like.

Also, writer Elliot S Maggin has dropped the exclamation mark from his name. The one that I've now convinced myself he always used.

I am, though, puzzled as to why our hero's depicted with closed eyes in every single panel he appears in.

In our second tale of the issue, Billy Batson's accompanied, on his mission to collect old periodicals for recycling, by his friend Sunny Sparkle - who, despite everything we're told about him, looks like something from a horror film - and his not so sunny cousin Rowdy. Among the material they gather on that collection is a book that tells you how to do everything.

Rowdy spots his opportunity and uses it to turn himself, instantly, into the world's toughest guy.

Clearly, this can't be allowed to stand and, so, Original Cap challenges the boy to a show of strength in which our hero tears apart the book that's given Rowdy his newfound power.

And, with the book destroyed, that newfound strength becomes newlost strength and whatever slight menace Rowdy may have posed to humanity is gone.

And this is noticeably different.

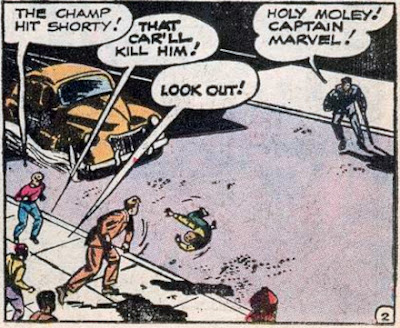

It's a big occasion for the local kids because, in the street, they spot a man who's only ever referred to as Champ who's clearly a boxer of some import.

He may be a champ in the ring but, out of it, he's made of 100% rotten and nearly gets an autograph-seeking child killed by knocking him into the path of a speedy automobile.

Fortunately, local newspaper vendor Freddy Freeman's on hand to become Captain Marvel Jr who then takes Champ off to have a word with him about this behaviour, doing most of his talking with his fists.

It's then that we learn Champ's agreed to throw his next fight but, happily, a random woman walks into the room and convinces him not to, by referencing his mother and father.

Who this woman is isn't made clear in the story. But Captain Marvel Jr clearly knows her. So, I'll assume she's his housekeeper or something.

Suitably shamed by her speech, Champ, with Jr's aid, quickly brings justice to the match-fixers, and Champ's a reformed character who's now even willing to talk to children.

It does leap out at you that this story has a far more serious attitude than the issue's other two, in both art and writing and does make you realise that Daredevil would never have existed had Captain Marvel Jr been around.

Overall, the book's a charming and simple read, like encountering a less demanding but cooler version of a 1970s Superman comic and, therefore, I give it the gentle Easter Sunday thumbs-up it, no doubt, deserves.

.jpg)

%20040a.jpg)