We all remember 2001: A Space Odyssey. It's the film which totally failed to predict the moon blasting out of Earth's orbit in 1999 and, thus, made a laughing stock of itself.

After a blunder like that, you'd have thought no one would want to create a sequel to it.

But you'd be wrong because someone did make a sequel to it. It was called 2010. Clearly, the intervening nine years hadn't been deemed worthy of cinematic immortality and didn't get movies named after them.

But that wasn't the only follow-up to the film because Marvel Comics produced ten sequels to it, in the form of a series written and drawn by Jack Kirby.

In some ways, Jack was the ideal man to helm a 2001 comic because the movie'd been filled with technology, Outer Space and Cosmic happenings.

It was also a movie which didn't rely on naturalistic dialogue, rational plotting or recognisable human behaviour. This also made it a good fit for Jack's writing style.

On the other hand, it could be argued Kirby was the worst man to do it because the film wasn't famous for its punch-ups, and he was.

So, how did the master of action acquit himself when it came to handling the more cerebral pretentiousness of a film you can usually only find meaning in while stoned?

I only had one chance to find out when I was a youth because I only ever came across one issue of the book, and that issue was #7 in which we get to meet the Space Seed.

Astronaut Gordon Pruett's stumbling around in his space suit when he decides to have a lie down and grow so old that he turns into a flying space baby.

In this guise, he floats around the universe, seeing wonders beyond measure before he descends upon a world whose populace have all but destroyed themselves in a global war.

Fortunately, they're not people to learn from their mistakes and, so, within minutes of the flying baby turning up, the last few survivors have pointlessly wiped each other out.

Not deterred by such silliness, the baby takes the remaining essence from the conflict's final two victims, flies off to an uninhabited world and drops it into the sea, in order to seed that planet with life. He then floats off into space, ready to do whatever it is he's planning to do next.

I have to hand it to Jack. He may have often seemed to be an improvisational writer but, here, he deftly balances his conflicting urges to be meaningful and to show people being blown up by hand grenades, by coming up with a tale which allows one of those elements to feed into the other. I'm not sure what it'd feel like to read ten issues of a book written like this but it works in isolation.

Having said that, It's hardly a mystery why the comic didn't last for more than ten issues. It really is difficult to not see the original movie as a creative dead end, in that it's a struggle to see where you could go with the story beyond what was in the film.

You can't further explore the nature or behaviour of the monolith without robbing it of its enigma - and its enigma is all it really has going for it.

Also, it can hardly be claimed there are any compelling human elements to the movie that would hold your interest. Not unless you've always considered Rising Damp to be a stealth sequel to the film, which explores what happened to Leonard Rossiter's character after he quit the space agency and decided to become a landlord.

Also, I'd struggle to claim it has themes which need further exploration because, beyond aliens interfering in human evolution, I don't have a clue what its themes actually are.

So, I think we have to view 2001 as another of those odd little books Marvel churned out in the 1970s, which were interesting experiments but were never going to actually go anywhere.

But I don't care. I'm personally glad it existed, because the world would be a poorer place in the absence of such idiosyncrasy.

Sunday, 29 December 2019

Thursday, 26 December 2019

December 26th, 1979 - Marvel UK, 40 years ago this week.

This week in 1979 was a week-and-a-half for British lovers of Americans in spandex because not only did we get to lay hands on all those lovely Marvel UK annuals of which I spoke in my last post but we also received a full complement of Marvel UK's regular weekly mags as well. Would life ever be this good again?

Yes it would - exactly a year later.

But, right now, it wasn't a year later.

It was right now.

And that's when I'm going to be taking a look at all those weekly books.

Right now.

Han and Chewie are trying to escape from a planet while concealing an unconscious Wookie in their cargo hold.

Well, they may be trying to escape from somewhere but Deathlok's doing the opposite. He's trying to get into somewhere, in his attempts kill Major Ryker.

The Guardians of the Galaxy are still battling the Reavers of Arcturus. This is all turning into an epic to rival the Kree/Skrull War itself.

Meanwhile, the Watcher's sharing with us the tale of how mankind discovers it can only flourish upon Earth and that it can like it or lump it.

Granted, the Watcher may not have used the phrase, "Like it or lump it."

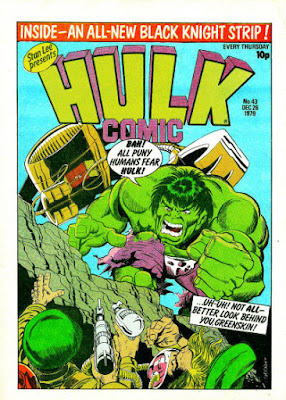

The Hulk's hanging around on Mount Rushmore and threatening to bump off the military, when the Goldbug shows up and offers him the treacherous hand of friendship.

We're still finding out why Captain Britain lost his memory.

Ant-Man's still fighting the Wasp who's now half-woman, half-insect and all angry.

The Surfer and Mephisto get properly acquainted.

And the female Defenders have their first clash with the Red Rajah.

Hooray! The Silurians make the cover of our favourite Time Lord related comic!

I do think the Silurian design's one of the greatest in the show's history and it's a shame it wasn't revived in the modern era.

Granted, they don't look anything like the reptiles they're supposed to be but who cares about that? You wouldn't want to bump into one in your living room and that's the acid test of a good monster.

Inside the comic, the Doctor's still having trouble with the City of the Damned.

Whether it's anywhere near the Village of the Damned is anyone's guess.

Marvel's adaptation of War of the Worlds reaches its finale. I predict the Martians will all die of a common cold.

There's also a text retelling of the ancient William Hartnell story Planet of Giants and more of the tale of The Stolen TARDIS.

Mysterio's trying to drown Spider-Man in his nursing home's swimming pool.

That's quite a fancy nursing home, if it has a swimming pool.

I quite fancy living there myself.

Admittedly, I'd have to put up with Mysterio trying to kill me to get his hands on my life savings but, hey-ho, there's a downside to everything.

Anyway, it all turns out the water's not real. It's all an illusion and Mysty's up to his usual tricks of trying to confound and confuse our hero.

Yes it would - exactly a year later.

But, right now, it wasn't a year later.

It was right now.

And that's when I'm going to be taking a look at all those weekly books.

Right now.

Han and Chewie are trying to escape from a planet while concealing an unconscious Wookie in their cargo hold.

Well, they may be trying to escape from somewhere but Deathlok's doing the opposite. He's trying to get into somewhere, in his attempts kill Major Ryker.

The Guardians of the Galaxy are still battling the Reavers of Arcturus. This is all turning into an epic to rival the Kree/Skrull War itself.

Meanwhile, the Watcher's sharing with us the tale of how mankind discovers it can only flourish upon Earth and that it can like it or lump it.

Granted, the Watcher may not have used the phrase, "Like it or lump it."

The Hulk's hanging around on Mount Rushmore and threatening to bump off the military, when the Goldbug shows up and offers him the treacherous hand of friendship.

We're still finding out why Captain Britain lost his memory.

Ant-Man's still fighting the Wasp who's now half-woman, half-insect and all angry.

The Surfer and Mephisto get properly acquainted.

And the female Defenders have their first clash with the Red Rajah.

Hooray! The Silurians make the cover of our favourite Time Lord related comic!

I do think the Silurian design's one of the greatest in the show's history and it's a shame it wasn't revived in the modern era.

Granted, they don't look anything like the reptiles they're supposed to be but who cares about that? You wouldn't want to bump into one in your living room and that's the acid test of a good monster.

Inside the comic, the Doctor's still having trouble with the City of the Damned.

Whether it's anywhere near the Village of the Damned is anyone's guess.

Marvel's adaptation of War of the Worlds reaches its finale. I predict the Martians will all die of a common cold.

There's also a text retelling of the ancient William Hartnell story Planet of Giants and more of the tale of The Stolen TARDIS.

Mysterio's trying to drown Spider-Man in his nursing home's swimming pool.

That's quite a fancy nursing home, if it has a swimming pool.

I quite fancy living there myself.

Admittedly, I'd have to put up with Mysterio trying to kill me to get his hands on my life savings but, hey-ho, there's a downside to everything.

Anyway, it all turns out the water's not real. It's all an illusion and Mysty's up to his usual tricks of trying to confound and confuse our hero.

Labels:

Marvel UK 40 years ago this week

Tuesday, 24 December 2019

Christmas Day, 1979 - Marvel UK, 40 years ago this week.

Hang onto your reindeers, Yule lovers, because it's Christmas!

Or it will be tomorrow!

And that gives me a perfect excuse to look at what our favourite comics company was serving up on Christmas Day 1979.

But, first, what else were we doing on that day?

BBC One, that morning, was giving us The Spinners at Christmas. This was, of course, not the American band of that name but the British one, famous for singing folk songs about Liverpool and doing blood donation adverts with jokes about skin colour you'd struggle to get away with these days.

We also got the Black Beauty movie, a documentary about Olympic ice skater John Curry, and the inevitable Christmas Day Top of the Pops, featuring Blondie, Boney M, Dr Hook, Lena Martell, Gary Numan, the Police, Cliff Richard, BA Robertson and Roxy Music, presented by Kid Jensen and Peter Powell.

That evening, the channel gave us The Mike Yarwood Christmas Show, To the Manor Born, The Sting and Parkinson at Christmas.

BBC Two, that afternoon, was giving us A Hard Day's Night, while, that evening, it unveiled A Christmas Carol and Baboushka.

The latter of those had nothing to do with the Kate Bush song of the same name but was a musical which presented the legend of a woman who gives hospitality to the Three Kings as they pass through on the way to Bethlehem. Too busy to join them, she says she'll follow on later but, when she finally gets there, it's too late and she's missed all the fun. The legend says she's still searching.

Personally, I'd give up if I were her. I think I'd conclude that, after two thousand years and Christ's crucifixion, the boat's well and truly sailed on that one.

To close off the evening, the channel gave us the film Cabaret.

Over on ITV, that morning, we received Lassie: The New Beginning and then, that afternoon, Christmas Oh Boy! with Joe Brown and the Bruvvers, Billy Hartman, Freddie "Fingers" Lee, Alvin Stardust, Shakin' Stevens, Rachel Sweet, Tim Witnall, Fumble, the Oh Boy! Cats and Kittens and the Oh Boy! Boogie Band. I would love to claim I know who Fumble were but I don't have a Scooby.

Also, that afternoon, the channel broadcast Goldfinger before taking us into the evening with the 3-2-1 Dickensian Xmas Show with Ted Rogers, Terry Scott, Bill Maynard and Wilfrid Brambell.

The evening saw George and Mildred, The Three Musketeers, Christmas with Eric and Ernie and Cleo Lane's Christmas. Not one person will be surprised to learn the big guest on the latter show was John Dankworth.

And the channel finished off the night by showing Death at Love House, a movie I cannot claim to have ever heard of.

But, of course, the big thing that everyone wanted to know was, what was the Christmas Number One?

Well, as I write these deathless words, in 2019, a song about sausage rolls is currently the UK's Christmas Number One but what of exactly 40 years ago? Could the 1970s possibly hope to match the cultural and societal impact of a song about sausage rolls?

No, they couldn't. We had to make do with Pink Floyd's Another Brick in the Wall Part 2 at Number One. It achieved this by gamely holding off ABBA's I Have a Dream. This meant that both the Christmas Number One and Number Two featured children singing on them. This is not a totally unknown phenomenon at Christmas.

The only actual Christmas songs on the chart that week were Paul McCartney's Wonderful Christmastime at 7, It Won't Seem Like Christmas by Elvis Presley at 25, Christmas Rappin' by Curtis Blow at 36 and A Merry Jingle by the Greedies at 47. Were the Greedies an unlikely team-up of Thin Lizzy and the Sex Pistols or am I just going mad?

So, those were the records we may have been unwrapping on that epic day but you know what else we all love to unwrap on Christmas Day?

Annuals!

And these were the ones Marvel UK had forced Santa to deliver to us.

This is a strange one, we get the whole of the Spidey vs Stegron vs Lizard story that, I think, involves the liberation of dinosaur skeletons in New York.

But that's not the strange thing. What is strange is that not all the annual's in full colour. Some pages are in a quaint combination of black, white and pink, creating a feel reminiscent of the days of the old Fleetway produced Marvel annuals of the very early 1970s.

On top of those reptilian antics, we get a text piece telling us all about Stan Lee's supreme and unique importance to the triumph of Marvel Comics and we also get a Spidey text story called Fun-House of Fear.

And the partial pinkness continues, as Marvel dishes out a reprint of the FF's first encounter with Salem's Seven.

There's also a cut-out Thing mask and a text story about our heroes fighting alien duplicates of themselves. I don't think the aliens are Skrulls but I cannot say that with certainty.

I do have to say that cover's almost identical to the one for last year's Fantastic Four annual.

And we get even more partially pink goodness.

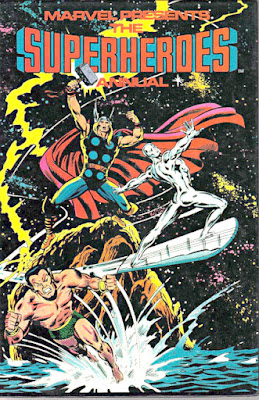

We also get Thor going to Hel to confront Hela about something or other.

We get the Silver Surfer vs the Abomination, which, as I've remarked on more than one occasion, may well have been the very first Marvel story I ever read, back in the ancient TV21 comic that predated even Mighty World of Marvel.

And we're also served up Sub-Mariner vs Tiger-Shark in a Marie Severin drawn tale.

But now here's where we get the real odd one out, as the only hint that this is an official Marvel publication is a copyright statement at the beginning of it.

Otherwise, it's definitely aimed at fans of the TV programme, rather than those of the comic, with heavy use of informational text and photo features about the show.

The picture strips that are included are clearly UK originated material and not all of them seem to be about the Hulk.

Mostly the book's in black and white, with occasional outbreaks of colour, giving it a very very British feel.

Or it will be tomorrow!

And that gives me a perfect excuse to look at what our favourite comics company was serving up on Christmas Day 1979.

But, first, what else were we doing on that day?

BBC One, that morning, was giving us The Spinners at Christmas. This was, of course, not the American band of that name but the British one, famous for singing folk songs about Liverpool and doing blood donation adverts with jokes about skin colour you'd struggle to get away with these days.

We also got the Black Beauty movie, a documentary about Olympic ice skater John Curry, and the inevitable Christmas Day Top of the Pops, featuring Blondie, Boney M, Dr Hook, Lena Martell, Gary Numan, the Police, Cliff Richard, BA Robertson and Roxy Music, presented by Kid Jensen and Peter Powell.

That evening, the channel gave us The Mike Yarwood Christmas Show, To the Manor Born, The Sting and Parkinson at Christmas.

BBC Two, that afternoon, was giving us A Hard Day's Night, while, that evening, it unveiled A Christmas Carol and Baboushka.

The latter of those had nothing to do with the Kate Bush song of the same name but was a musical which presented the legend of a woman who gives hospitality to the Three Kings as they pass through on the way to Bethlehem. Too busy to join them, she says she'll follow on later but, when she finally gets there, it's too late and she's missed all the fun. The legend says she's still searching.

Personally, I'd give up if I were her. I think I'd conclude that, after two thousand years and Christ's crucifixion, the boat's well and truly sailed on that one.

To close off the evening, the channel gave us the film Cabaret.

Over on ITV, that morning, we received Lassie: The New Beginning and then, that afternoon, Christmas Oh Boy! with Joe Brown and the Bruvvers, Billy Hartman, Freddie "Fingers" Lee, Alvin Stardust, Shakin' Stevens, Rachel Sweet, Tim Witnall, Fumble, the Oh Boy! Cats and Kittens and the Oh Boy! Boogie Band. I would love to claim I know who Fumble were but I don't have a Scooby.

Also, that afternoon, the channel broadcast Goldfinger before taking us into the evening with the 3-2-1 Dickensian Xmas Show with Ted Rogers, Terry Scott, Bill Maynard and Wilfrid Brambell.

The evening saw George and Mildred, The Three Musketeers, Christmas with Eric and Ernie and Cleo Lane's Christmas. Not one person will be surprised to learn the big guest on the latter show was John Dankworth.

And the channel finished off the night by showing Death at Love House, a movie I cannot claim to have ever heard of.

But, of course, the big thing that everyone wanted to know was, what was the Christmas Number One?

Well, as I write these deathless words, in 2019, a song about sausage rolls is currently the UK's Christmas Number One but what of exactly 40 years ago? Could the 1970s possibly hope to match the cultural and societal impact of a song about sausage rolls?

No, they couldn't. We had to make do with Pink Floyd's Another Brick in the Wall Part 2 at Number One. It achieved this by gamely holding off ABBA's I Have a Dream. This meant that both the Christmas Number One and Number Two featured children singing on them. This is not a totally unknown phenomenon at Christmas.

The only actual Christmas songs on the chart that week were Paul McCartney's Wonderful Christmastime at 7, It Won't Seem Like Christmas by Elvis Presley at 25, Christmas Rappin' by Curtis Blow at 36 and A Merry Jingle by the Greedies at 47. Were the Greedies an unlikely team-up of Thin Lizzy and the Sex Pistols or am I just going mad?

So, those were the records we may have been unwrapping on that epic day but you know what else we all love to unwrap on Christmas Day?

Annuals!

And these were the ones Marvel UK had forced Santa to deliver to us.

This is a strange one, we get the whole of the Spidey vs Stegron vs Lizard story that, I think, involves the liberation of dinosaur skeletons in New York.

But that's not the strange thing. What is strange is that not all the annual's in full colour. Some pages are in a quaint combination of black, white and pink, creating a feel reminiscent of the days of the old Fleetway produced Marvel annuals of the very early 1970s.

On top of those reptilian antics, we get a text piece telling us all about Stan Lee's supreme and unique importance to the triumph of Marvel Comics and we also get a Spidey text story called Fun-House of Fear.

And the partial pinkness continues, as Marvel dishes out a reprint of the FF's first encounter with Salem's Seven.

There's also a cut-out Thing mask and a text story about our heroes fighting alien duplicates of themselves. I don't think the aliens are Skrulls but I cannot say that with certainty.

I do have to say that cover's almost identical to the one for last year's Fantastic Four annual.

And we get even more partially pink goodness.

We also get Thor going to Hel to confront Hela about something or other.

We get the Silver Surfer vs the Abomination, which, as I've remarked on more than one occasion, may well have been the very first Marvel story I ever read, back in the ancient TV21 comic that predated even Mighty World of Marvel.

And we're also served up Sub-Mariner vs Tiger-Shark in a Marie Severin drawn tale.

But now here's where we get the real odd one out, as the only hint that this is an official Marvel publication is a copyright statement at the beginning of it.

Otherwise, it's definitely aimed at fans of the TV programme, rather than those of the comic, with heavy use of informational text and photo features about the show.

The picture strips that are included are clearly UK originated material and not all of them seem to be about the Hulk.

Mostly the book's in black and white, with occasional outbreaks of colour, giving it a very very British feel.

Labels:

Annuals,

Marvel UK,

Marvel UK 40 years ago this week

Sunday, 22 December 2019

2000 AD - November 1981.

Hark! What's that sound at the door?

It's the knock of the television license detector van man - and he wants a word with you.

He doesn't really because, as we all now know, TV license detector vans never existed - what with them being a scientific impossibility.

However, you may not have known that, way back in November 1981 and, if you didn't, you may have been living in fear because that was the month in which the colour TV license increased from £34 to £46. Meanwhile, the license for a black and white set rose from a walloping great £12 to a walloping greater £15.

With those sorts of prices, there was only one thing for it. We were all going to have to seek refuge in the cinemas which saw the release of two movies of a very different hue; Time Bandits and Porky's.

Being part of the intellectual elite, I do, of course, prefer Time Bandits. Admittedly, I've never actually seen Porky's and suspect I've spent most of my life getting it mixed up with Animal House.

Thinking about it, I don't think I've seen Animal House either.

I, therefore, have no valid opinion about either movie.

What I definitely did see in that month was the UK singles chart.

And what a volatile thing it was proving to be. November kicked off with the top spot in the hands of Dave Stewart and Barbara Gaskin's It's My Party before that was quickly slain by the Police's Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic. However, that record's reign was also brief, as it was quickly deposed by Queen and David Bowie's Under Pressure, a track which, in retrospect, began the early 1980s trend for established artists teaming up in order to sell more records than they could on their own.

But that tactic was only a temporary triumph for Queen and Bowie because, almost as soon as it topped the chart, the track was dethroned by Julio Iglesias' Begin the Beguine which found itself gripping the Number One slot in the final week of that month.

Things were far less lively on the album chart because November began with the top spot in the hands of Shakin' Stevens' Shaky which was then dislodged for the rest of the month by Queen's Greatest Hits.

Clearly, there was no shortage of activity in the worlds of TV, cinema and music but what of the realm of picture strips in that year's penultimate month? Just what doings were afoot in the galaxy's greatest comic?

We were still getting a diet of Ace Trucking Co, Mean Arena, Tharg's Future Shocks, Judge Dredd, Nemesis the Warlock and Rogue Trooper. Dredd was still in the throes of Block Mania, although Max Normal appeared not to be.

But perhaps the most intriguing development was in Progs 237 and 238 which featured a strip about someone called Abelard Snazz from the trusty typewriter of Alan Moore. I must confess I've no recollection of this strip at all but have no doubt it was a thing of wonder to behold.

Still, surely the most exciting news came with Prog 239 which gave us all a chance to wear a Cosmic Wars watch.

If only I knew what Cosmic Wars was.

It's the knock of the television license detector van man - and he wants a word with you.

He doesn't really because, as we all now know, TV license detector vans never existed - what with them being a scientific impossibility.

However, you may not have known that, way back in November 1981 and, if you didn't, you may have been living in fear because that was the month in which the colour TV license increased from £34 to £46. Meanwhile, the license for a black and white set rose from a walloping great £12 to a walloping greater £15.

With those sorts of prices, there was only one thing for it. We were all going to have to seek refuge in the cinemas which saw the release of two movies of a very different hue; Time Bandits and Porky's.

Being part of the intellectual elite, I do, of course, prefer Time Bandits. Admittedly, I've never actually seen Porky's and suspect I've spent most of my life getting it mixed up with Animal House.

Thinking about it, I don't think I've seen Animal House either.

I, therefore, have no valid opinion about either movie.

What I definitely did see in that month was the UK singles chart.

And what a volatile thing it was proving to be. November kicked off with the top spot in the hands of Dave Stewart and Barbara Gaskin's It's My Party before that was quickly slain by the Police's Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic. However, that record's reign was also brief, as it was quickly deposed by Queen and David Bowie's Under Pressure, a track which, in retrospect, began the early 1980s trend for established artists teaming up in order to sell more records than they could on their own.

But that tactic was only a temporary triumph for Queen and Bowie because, almost as soon as it topped the chart, the track was dethroned by Julio Iglesias' Begin the Beguine which found itself gripping the Number One slot in the final week of that month.

Things were far less lively on the album chart because November began with the top spot in the hands of Shakin' Stevens' Shaky which was then dislodged for the rest of the month by Queen's Greatest Hits.

Clearly, there was no shortage of activity in the worlds of TV, cinema and music but what of the realm of picture strips in that year's penultimate month? Just what doings were afoot in the galaxy's greatest comic?

We were still getting a diet of Ace Trucking Co, Mean Arena, Tharg's Future Shocks, Judge Dredd, Nemesis the Warlock and Rogue Trooper. Dredd was still in the throes of Block Mania, although Max Normal appeared not to be.

But perhaps the most intriguing development was in Progs 237 and 238 which featured a strip about someone called Abelard Snazz from the trusty typewriter of Alan Moore. I must confess I've no recollection of this strip at all but have no doubt it was a thing of wonder to behold.

Still, surely the most exciting news came with Prog 239 which gave us all a chance to wear a Cosmic Wars watch.

If only I knew what Cosmic Wars was.

Thursday, 19 December 2019

December 19th, 1979 - Marvel UK, 40 years ago this week.

Forty years ago this week, London was drowning and I had no fear.

That's mostly because I wasn't in London.

The Clash were, though and, to prove it, they released their seminal Post-Punk LP London Calling.

And it wasn't only calling to us, it was calling to the lord of all vampires too because, on this night in 1979, BBC One was airing its two-part adaptation of Count Dracula, starring Louis Jourdan and Susan Penhaligon. How well I remember watching it.

Admittedly, when I say I remember watching it, I remember watching but don't actually recall anything that happened in it. I've no doubt, however, that it followed the tried-and-tested route of estate agents, sea crossings, Whitby wanderings and stakings we all love and fear.

The big mystery is in the credits. According to them, it also featured Gareth Hunt in a role billed as, "Small Boy." Surely Gareth Hunt was about thirty when this was made. How, exactly, did he manage to play a small boy?

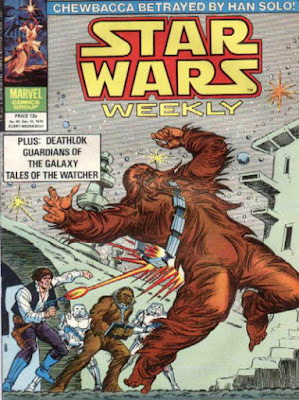

Quick! Get the space police! Some sort of Wookie fight seems to have broken out!

My razor-sharp senses tell me the cover image is set on the Wookie home world.

I can say that because I recognise those background tree buildings from the Star Wars Holiday Special which came up in conversation on this site, the other day.

Beyond that, I can say nothing of this tale.

Elsewhere, I believe the Guardians of the Galaxy are still trying to defeat the Reavers of Arcturus.

They're taking their time about it. How hard can it be?

An injured Deathlok goes to see his wife who's been, up until now, totally oblivious to his science-spawned transformation. I believe that, when she finds out, she doesn't take the news well.

In this week's Tales of the Watcher, a bunch of space travellers get kidnapped by trees and have to be rescued by the one member of their party who recommended caution when it came to exploring this brave new world.

At the old folks' home, Mysterio finally reveals the truth of who he is, to the burglar who killed Uncle Ben.

As there's a whole bucketful of Mysterioes on the cover, I suspect the reader won't be as shocked by the revelation as the burglar is.

Goldbug's making his dastardly plans to kidnap the Hulk so he can get to the Andes and, presumably, lay his hands on all the lovely gold Eldorado has to offer.

Ant-Man and the Wasp are still stuck at insect size and still trying to defeat the alcoholic android that's holding them captive.

The Black Knight and Merlin are trying to get to the root of why Captain Britain's lost his memory.

The Silver Surfer's finally come face-to-face with Mephisto. Can he possibly hope to defeat the mighty master of evil?

The Defenders are squaring up to the Red Rajah while, back at Dr Strange's house, Hellcat's teaming up with the Valkyrie and Red Guardian.

Hooray! Davros has made the front cover! I'm such a saddo that I've noticed they've reversed the image because he's got his wrong hand working.

However, in the main strip, the Doctor's still having trouble with the City of the Damned.

There's also the chance to win a hundred annuals.

I assume that doesn't mean each.

Marvel's adaptation of War of the Worlds is still going.

We get a text adaptation of whichever William Hartnell story it was that featured the French Revolution. Was it The Reign of Terror?

And we get more of the picture strip which details the story of the stolen TARDIS.

That's mostly because I wasn't in London.

The Clash were, though and, to prove it, they released their seminal Post-Punk LP London Calling.

And it wasn't only calling to us, it was calling to the lord of all vampires too because, on this night in 1979, BBC One was airing its two-part adaptation of Count Dracula, starring Louis Jourdan and Susan Penhaligon. How well I remember watching it.

Admittedly, when I say I remember watching it, I remember watching but don't actually recall anything that happened in it. I've no doubt, however, that it followed the tried-and-tested route of estate agents, sea crossings, Whitby wanderings and stakings we all love and fear.

The big mystery is in the credits. According to them, it also featured Gareth Hunt in a role billed as, "Small Boy." Surely Gareth Hunt was about thirty when this was made. How, exactly, did he manage to play a small boy?

Quick! Get the space police! Some sort of Wookie fight seems to have broken out!

My razor-sharp senses tell me the cover image is set on the Wookie home world.

I can say that because I recognise those background tree buildings from the Star Wars Holiday Special which came up in conversation on this site, the other day.

Beyond that, I can say nothing of this tale.

Elsewhere, I believe the Guardians of the Galaxy are still trying to defeat the Reavers of Arcturus.

They're taking their time about it. How hard can it be?

An injured Deathlok goes to see his wife who's been, up until now, totally oblivious to his science-spawned transformation. I believe that, when she finds out, she doesn't take the news well.

In this week's Tales of the Watcher, a bunch of space travellers get kidnapped by trees and have to be rescued by the one member of their party who recommended caution when it came to exploring this brave new world.

At the old folks' home, Mysterio finally reveals the truth of who he is, to the burglar who killed Uncle Ben.

As there's a whole bucketful of Mysterioes on the cover, I suspect the reader won't be as shocked by the revelation as the burglar is.

Goldbug's making his dastardly plans to kidnap the Hulk so he can get to the Andes and, presumably, lay his hands on all the lovely gold Eldorado has to offer.

Ant-Man and the Wasp are still stuck at insect size and still trying to defeat the alcoholic android that's holding them captive.

The Black Knight and Merlin are trying to get to the root of why Captain Britain's lost his memory.

The Silver Surfer's finally come face-to-face with Mephisto. Can he possibly hope to defeat the mighty master of evil?

The Defenders are squaring up to the Red Rajah while, back at Dr Strange's house, Hellcat's teaming up with the Valkyrie and Red Guardian.

Hooray! Davros has made the front cover! I'm such a saddo that I've noticed they've reversed the image because he's got his wrong hand working.

However, in the main strip, the Doctor's still having trouble with the City of the Damned.

There's also the chance to win a hundred annuals.

I assume that doesn't mean each.

Marvel's adaptation of War of the Worlds is still going.

We get a text adaptation of whichever William Hartnell story it was that featured the French Revolution. Was it The Reign of Terror?

And we get more of the picture strip which details the story of the stolen TARDIS.

Labels:

Marvel UK 40 years ago this week

Tuesday, 17 December 2019

The 2019 Special Christmas Post! Never settle for second best. You don't need to, because I'm about to do it for you.

Because you The Reader demanded it, here it is; this year's Christmas song post!

Granted, there's a certain problem with such a thing, as, last year, I did one demanding to know your favourite Christmas song of all time.

Obviously, because I've already done it, I can't do that again - even though I want to - so I've hit upon an idea no one has ever had in the entire history of mankind!

And that's demanding to know what your second favourite Christmas song is.

What's that noise you hear on your rooftop? Is it the sound of Rudolph's hooves scraping on the slates, as Santa comes to deliver your presents?

Why, no, it's the sound of this site scraping the bottom of the barrel.

But, then again, perhaps it's not, because this now means that, next year, I'm going to be able to ask you for your third favourite Christmas song of all time. I can't wait for the year 2145 when I can, at last, discover the identity of your 127th favourite Christmas song.

Anyway, the second best Christmas song of all time. For me, it's an easy one because, if you have Slade's Merry Xmas Everybody as your Number One, as I did last year, there's only one record you can have as your Number Two.

And that's Wizzard's I Wish it Could Be Christmas Everyday. Has there ever been a catchier, bouncier, more joyous and successful attempt to capture the mood of a British Yuletide?

Yes there has; Slade's Merry Xmas Everybody.

But, that one aside, has there ever been a better attempt than this one?

No, there hasn't. The moment I hear that cash register open at the beginning of the track, I know the season of magic and goodwill is once more upon us.

But it does always strike me as being amazing that, arguably, the two greatest British Christmas songs of all time were written by men born within 12 miles of each other and mere months apart - and that those records were released in exactly the same month, December 1973.

It also amazes me to think that, had Roy Wood not fled ELO when he did, this would have been an ELO single.

Then again, it also amazes me that he was only 27 at the time. How does any man look that old at 27?

Anyway, those are my thoughts on the matter. You may have thoughts of your own, and you're free to express them below.

For that matter, you're free to express any thoughts you may have about any Christmas songs, because it's Christmas, and Christmas is meant for sharing.

Sunday, 15 December 2019

The Champions #12 - The Stranger Strikes!

The Marvel Comics company has many great super-hero teams but none are better than the Champions.

I know this because they're called the Champions and that must mean they're the best.

Right?

Well, perhaps not. If ever Marvel had a useless super-hero team, it had to be this bunch who just seemed to be made up of whatever super-doers the company had hanging around and out of work.

As that was basically the function of the Defenders, and these heroes weren't even interesting enough to get into that team, you have to suspect this outfit really is fighting a lost cause.

Also, in what mad world are Ghost Rider, the Angel, Iceman, Hercules, Black Widow and a blonde Russian woman whose name I've forgotten, a logical combination of talents?

Still, I'm nothing if not a lover of plucky underdogs and I did, in my youth, have a couple of issues of their mag.

One of those was #12 which featured not one but three epic clashes, jam-packed into just a single tale. So, all these years later, just what do my shattered senses make of it?

We join the action midway through, as the Champions catch up with Black Goliath and help him fight Stilt-Man.

When I say, "Help," despite there being six of them and one of them being Hercules, they prove to be no assistance at all and, in the end, Black Goliath has to chase off after Stilt-Man on his own while the Champions, who he's got fed up of and told to shove off, lose interest in the fight and return to their massive headquarters, for some quality Me Time.

I think I'm starting to see why they're not one of Marvel's most revered teams. I can't see the Avengers just losing interest in a fight and going off home while leaving a rookie to fight a villain that all six of them combined couldn't stop.

Anyway, when they get back to their HQ, they find they have a visitor, a young woman called Reggie Clayborne who has a box her love interest stole from Tony Stark's factory. Barely has she finished expositing all over them than the object inside the box starts to rapidly expand and then the Stranger walks in through the wall, declaring that he's there to help them.

Needless to say, that's the cue for the Champions to start trying to smash his face in because... ...ah, why not? They're Marvel heroes. What else are they going to do?

Needless to say, the team that couldn't stop Stilt-Man doesn't get very far with thwarting one of the universe's most powerful beings.

However, the rapidly expanding object does and, as it starts to swallow up the Stranger, he tells them it's a weird kind of bomb he once built and that it'll expand until it encapsulates the whole solar system and then turn solid and contract and kill them all - even Stilt-Man!

Realising this might not be a good thing, they agree to go off somewhere to get the one object the Stranger says will fix things. And, with his magic wavy hand, the Stranger sends them to a far-off world to do it.

Unfortunately, when they get there, they quickly discover that world belongs to Kamo Tharn and his horde and now he's going to try and kill them!

It's a story that's not short of incident. Not many comics would start with a fight against one foe, abandon it halfway through, introduce the Stranger, launch into a whole new storyline and then fling its heroes into a totally different world, to face their third foe of the issue.

This does, at least, mean you don't get bored.

But this might be its main problem.

It's a bit too conflicty.

Not only do we get the clashes with Stilt-Man, the Stranger and Kamo Tharn but the Champions themselves seem to be constantly at odds with each other. It's clear the Angel doesn't like being told what to do by Iceman, Ghost Rider doesn't trust the blonde Russian woman whose name I can't remember, and the Black Widow, at one point, tells off Ghost Rider for getting in her way. It's like, seriously, can't we all take a chill pill?

Still, in fairness, the tale does make you want to read next month's issue, to find out just how the problem of the expanding bomb gets solved.

John Byrne's art is, of course, perfectly pleasing to the eye. It seems to lack detail compared to some of his other work, suggesting he might not be giving it everything. Or maybe that's just how he was drawing things at this particular stage of his career.

Main annoyances of the tale are the sight of seven super-heroes totally failing to make any headway against a foe who gets beaten up by Daredevil every six months, and the fact we're never told who the blonde Russian woman actually is. I've seen her before, in some Hulk story or other but her name escapes me.

Still, I've always liked the Stranger, even if he's quite annoying. It's just a shame we don't get to see more of him before he's swallowed up.

I know this because they're called the Champions and that must mean they're the best.

Right?

Well, perhaps not. If ever Marvel had a useless super-hero team, it had to be this bunch who just seemed to be made up of whatever super-doers the company had hanging around and out of work.

As that was basically the function of the Defenders, and these heroes weren't even interesting enough to get into that team, you have to suspect this outfit really is fighting a lost cause.

Also, in what mad world are Ghost Rider, the Angel, Iceman, Hercules, Black Widow and a blonde Russian woman whose name I've forgotten, a logical combination of talents?

Still, I'm nothing if not a lover of plucky underdogs and I did, in my youth, have a couple of issues of their mag.

One of those was #12 which featured not one but three epic clashes, jam-packed into just a single tale. So, all these years later, just what do my shattered senses make of it?

We join the action midway through, as the Champions catch up with Black Goliath and help him fight Stilt-Man.

When I say, "Help," despite there being six of them and one of them being Hercules, they prove to be no assistance at all and, in the end, Black Goliath has to chase off after Stilt-Man on his own while the Champions, who he's got fed up of and told to shove off, lose interest in the fight and return to their massive headquarters, for some quality Me Time.

I think I'm starting to see why they're not one of Marvel's most revered teams. I can't see the Avengers just losing interest in a fight and going off home while leaving a rookie to fight a villain that all six of them combined couldn't stop.

Anyway, when they get back to their HQ, they find they have a visitor, a young woman called Reggie Clayborne who has a box her love interest stole from Tony Stark's factory. Barely has she finished expositing all over them than the object inside the box starts to rapidly expand and then the Stranger walks in through the wall, declaring that he's there to help them.

Needless to say, that's the cue for the Champions to start trying to smash his face in because... ...ah, why not? They're Marvel heroes. What else are they going to do?

Needless to say, the team that couldn't stop Stilt-Man doesn't get very far with thwarting one of the universe's most powerful beings.

However, the rapidly expanding object does and, as it starts to swallow up the Stranger, he tells them it's a weird kind of bomb he once built and that it'll expand until it encapsulates the whole solar system and then turn solid and contract and kill them all - even Stilt-Man!

Realising this might not be a good thing, they agree to go off somewhere to get the one object the Stranger says will fix things. And, with his magic wavy hand, the Stranger sends them to a far-off world to do it.

Unfortunately, when they get there, they quickly discover that world belongs to Kamo Tharn and his horde and now he's going to try and kill them!

It's a story that's not short of incident. Not many comics would start with a fight against one foe, abandon it halfway through, introduce the Stranger, launch into a whole new storyline and then fling its heroes into a totally different world, to face their third foe of the issue.

This does, at least, mean you don't get bored.

But this might be its main problem.

It's a bit too conflicty.

Not only do we get the clashes with Stilt-Man, the Stranger and Kamo Tharn but the Champions themselves seem to be constantly at odds with each other. It's clear the Angel doesn't like being told what to do by Iceman, Ghost Rider doesn't trust the blonde Russian woman whose name I can't remember, and the Black Widow, at one point, tells off Ghost Rider for getting in her way. It's like, seriously, can't we all take a chill pill?

Still, in fairness, the tale does make you want to read next month's issue, to find out just how the problem of the expanding bomb gets solved.

John Byrne's art is, of course, perfectly pleasing to the eye. It seems to lack detail compared to some of his other work, suggesting he might not be giving it everything. Or maybe that's just how he was drawing things at this particular stage of his career.

Main annoyances of the tale are the sight of seven super-heroes totally failing to make any headway against a foe who gets beaten up by Daredevil every six months, and the fact we're never told who the blonde Russian woman actually is. I've seen her before, in some Hulk story or other but her name escapes me.

Still, I've always liked the Stranger, even if he's quite annoying. It's just a shame we don't get to see more of him before he's swallowed up.

Thursday, 12 December 2019

December 12th, 1979 - Marvel UK, 40 years ago this week.

Have you ever wondered what happened to bigpox?

I've no idea what happened to bigpox.

I do, however, know what happened to smallpox.

It was murdered.

It was murdered on December 9th 1979 when its eradication was officially certified, making it the first human disease ever to have been driven to extinction.

That was clearly a thing to celebrate - especially for milkmaids - and another thing to celebrate that week was British stunt rider Eddie Kidd successfully jumping 80 ft on a motorcycle. I have no more information on that feat, as the Wikipedia page I was looking at furnished no more information but it sounds like it's probably a thing worth boasting about.

Elsewhere, that week, the unrecognised state of Zimbabwe Rhodesia returned to British control and switched back to the name, "Southern Rhodesia." Lord Soames was appointed transitional governor to oversee its move to independence and inspire the last Stevie Wonder song that I actually liked.

Speaking of songs, the summit of the UK singles chart that week belonged to Pink Floyd's Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2.

Amazingly, with just thirteen days to go until Santa's birthday, there was only one Christmas song in the Top 40. That was Wonderful Christmastime by that bloke who used to be in the Beatles.

What's this? Han Solo shooting Chewbacca, dead, in the back?

I've a suspicion that's not really Chewbacca but some random Wookie, and that Marvel's merely playing games with us.

On the other hand, if it is Chewie, then it's one hell of a plot twist and I'd love to know how they wrote their way out of that one when he showed up, alive and well, in the next movie.

Elsewhere, the Guardians of the Galaxy are still battling the Reavers of Arcturus in a story which seems to have been going on since the dawn of time.

Deathlok's still battling War-Wolf. I suspect that battle will be shorter lived.

As will War-Wolf.

In this week's Tales of the Watcher, a Martian comes to Earth and triumphantly destroys an Earth rocket...

...only for it to turn out he's merely destroyed a toy because he's only an inch tall and doesn't realise it.

The Corporation finally dealt with and his fight with Machine Man over, it's now time for the Hulk to launch into his journey to the Andes, which'll see the rejuvenation of Tyrannus - or, "Des," as we're now to call him.

Maybe it's my imagination but I'm sure this comic's already reprinted this story. I'm fairly sure it was the first Hulk tale it published when it dropped the UK originated adventures and switched back to US material.

The Wasp and Ant-Man are still trapped at insect-size and being held captive by a drunk and lonely robot who wants to gain the powers of insects.

The comic's still giving us the backstory of the Black Knight, while the Defenders are about to confront the Red Rajah, with Hellcat showing up to join in.

Hooray! We get a text article on one of my favourite Doctor Who monsters, the Zygons, who looked a lot creepier in the old shows than they do in the modern ones. Adding fangs was just overkill. As was the angry facial expression.

We also get a Dave Gibbons drawn tale called City of the Damned. I don't know if it's anywhere near The City of Death.

The War of the Worlds adaptation's still going.

We also get a text piece about 1960s story The Sensorites and, also, a new picture strip called The Stolen TARDIS.

My knowledge of this issue is highly patchy but I do know the main tale sees the Kingpin out to kill Spider-Man before the clock strikes midnight, or his wife Vanessa will treat him like a pumpkin.

I've no idea what happened to bigpox.

I do, however, know what happened to smallpox.

It was murdered.

It was murdered on December 9th 1979 when its eradication was officially certified, making it the first human disease ever to have been driven to extinction.

That was clearly a thing to celebrate - especially for milkmaids - and another thing to celebrate that week was British stunt rider Eddie Kidd successfully jumping 80 ft on a motorcycle. I have no more information on that feat, as the Wikipedia page I was looking at furnished no more information but it sounds like it's probably a thing worth boasting about.

Elsewhere, that week, the unrecognised state of Zimbabwe Rhodesia returned to British control and switched back to the name, "Southern Rhodesia." Lord Soames was appointed transitional governor to oversee its move to independence and inspire the last Stevie Wonder song that I actually liked.

Speaking of songs, the summit of the UK singles chart that week belonged to Pink Floyd's Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2.

Amazingly, with just thirteen days to go until Santa's birthday, there was only one Christmas song in the Top 40. That was Wonderful Christmastime by that bloke who used to be in the Beatles.

What's this? Han Solo shooting Chewbacca, dead, in the back?

I've a suspicion that's not really Chewbacca but some random Wookie, and that Marvel's merely playing games with us.

On the other hand, if it is Chewie, then it's one hell of a plot twist and I'd love to know how they wrote their way out of that one when he showed up, alive and well, in the next movie.

Elsewhere, the Guardians of the Galaxy are still battling the Reavers of Arcturus in a story which seems to have been going on since the dawn of time.

Deathlok's still battling War-Wolf. I suspect that battle will be shorter lived.

As will War-Wolf.

In this week's Tales of the Watcher, a Martian comes to Earth and triumphantly destroys an Earth rocket...

...only for it to turn out he's merely destroyed a toy because he's only an inch tall and doesn't realise it.

The Corporation finally dealt with and his fight with Machine Man over, it's now time for the Hulk to launch into his journey to the Andes, which'll see the rejuvenation of Tyrannus - or, "Des," as we're now to call him.

Maybe it's my imagination but I'm sure this comic's already reprinted this story. I'm fairly sure it was the first Hulk tale it published when it dropped the UK originated adventures and switched back to US material.

The Wasp and Ant-Man are still trapped at insect-size and being held captive by a drunk and lonely robot who wants to gain the powers of insects.

The comic's still giving us the backstory of the Black Knight, while the Defenders are about to confront the Red Rajah, with Hellcat showing up to join in.

Hooray! We get a text article on one of my favourite Doctor Who monsters, the Zygons, who looked a lot creepier in the old shows than they do in the modern ones. Adding fangs was just overkill. As was the angry facial expression.

We also get a Dave Gibbons drawn tale called City of the Damned. I don't know if it's anywhere near The City of Death.

The War of the Worlds adaptation's still going.

We also get a text piece about 1960s story The Sensorites and, also, a new picture strip called The Stolen TARDIS.

My knowledge of this issue is highly patchy but I do know the main tale sees the Kingpin out to kill Spider-Man before the clock strikes midnight, or his wife Vanessa will treat him like a pumpkin.

Labels:

Marvel UK 40 years ago this week

Tuesday, 10 December 2019

The Marvel Lucky Bag - December 1979.

Are you a big fan of boldly going where no man has gone before?

If so, this month in 1979 was perfect for you because it saw the launch of Star Trek: The Motion Picture, the cinematic masterpiece which proved that space exploration could be just as dull as staying at home.

But, if you didn't want to go all the way to the cinema, a trip to the newsagents might suffice instead.

And that's because the event had already been prepared for by one thing.

And that thing was...

...Marvel giving us its adaptation of that non-stop thrill-ride. I like to think that a full ten pages are devoted to the Enterprise leaving dry dock, in honour of the movie's glacial pacing.

As if that's not enough for us, this book also contains an interview with Jesco von Puttkamer.

I don't have a clue who Jesco von Puttkamer is.

Also, the other likenesses are fine but that really doesn't look like William Shatner on the cover.

Perhaps it's Jesco von Puttkamer.

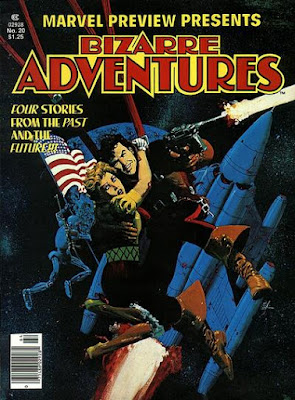

As far as I can make out, we get a whole heap of Howard Chaykin's Dominic Fortune.

But more excitingly for me, we also get War Toy and Good Lord, as made famous by their appearances in Marvel UK's Planet of the Apes comic.

Of course, neither of those tales has anything to do with Planet of the Apes - one being about the death of a military robot and the other involving space explorers accidentally killing God.

Regardless, they're two of the most memorable back-up strips ever to have featured in that book and I salute them both.

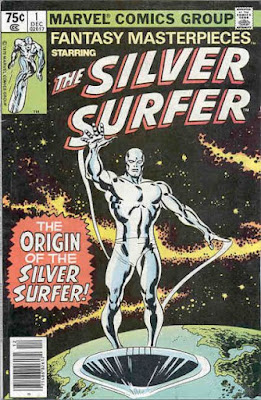

Marvel shows an admirable willingness to cash-in on its heritage by launching a series of Silver Surfer reprints, beginning with his origin, from 1968.

Clearly seeing 1968 reprints as the way ahead, as we approach the 1980s, Marvel also decides to reprint Namor's series from that year.

Hold on. Wait. What? Now the company's launching a run of X-Men reprints as well? Has the House of Ideas completely run out of new things to publish?

Oh well, at least it's not from 1968.

Just to prove Marvel is actually capable of throwing at least one new thing at us, we get the launch of ROM's very own comic.

I must confess I always get ROM mixed up with Machine Man, even though they're completely different characters.

I've never read this comic, nor any other book featuring the character but I believe that, this issue, the robot arrives on Earth and kills a bunch of people before it turns out they're not people at all. They're aliens too, and, therefore don't matter.

He also gets to take on the National Guard while he's at it.

This comic, almost inevitably, is drawn by Sal Buscema.

Now that Jack Kirby's gone, Marvel clearly feels it's safe to relaunch the Black Panther's strip, carrying on where Don McGregor's run left off, with the conclusion of T'Challa's struggles with the Ku Klux Klan.

I suspect that magic frogs will not feature heavily in this story.

However, those hoping for a healthy dose of Don McGregor's vigorous verbosity are doomed to disappointment, as the tale's written by Ed Hannigan.

Then again, perhaps Ed has the sense to give us what we all want, and decides to emulate Don's writing style.

If so, this month in 1979 was perfect for you because it saw the launch of Star Trek: The Motion Picture, the cinematic masterpiece which proved that space exploration could be just as dull as staying at home.

But, if you didn't want to go all the way to the cinema, a trip to the newsagents might suffice instead.

And that's because the event had already been prepared for by one thing.

And that thing was...

...Marvel giving us its adaptation of that non-stop thrill-ride. I like to think that a full ten pages are devoted to the Enterprise leaving dry dock, in honour of the movie's glacial pacing.

As if that's not enough for us, this book also contains an interview with Jesco von Puttkamer.

I don't have a clue who Jesco von Puttkamer is.

Also, the other likenesses are fine but that really doesn't look like William Shatner on the cover.

Perhaps it's Jesco von Puttkamer.

As far as I can make out, we get a whole heap of Howard Chaykin's Dominic Fortune.

But more excitingly for me, we also get War Toy and Good Lord, as made famous by their appearances in Marvel UK's Planet of the Apes comic.

Of course, neither of those tales has anything to do with Planet of the Apes - one being about the death of a military robot and the other involving space explorers accidentally killing God.

Regardless, they're two of the most memorable back-up strips ever to have featured in that book and I salute them both.

Marvel shows an admirable willingness to cash-in on its heritage by launching a series of Silver Surfer reprints, beginning with his origin, from 1968.

Clearly seeing 1968 reprints as the way ahead, as we approach the 1980s, Marvel also decides to reprint Namor's series from that year.

Hold on. Wait. What? Now the company's launching a run of X-Men reprints as well? Has the House of Ideas completely run out of new things to publish?

Oh well, at least it's not from 1968.

Just to prove Marvel is actually capable of throwing at least one new thing at us, we get the launch of ROM's very own comic.

I must confess I always get ROM mixed up with Machine Man, even though they're completely different characters.

I've never read this comic, nor any other book featuring the character but I believe that, this issue, the robot arrives on Earth and kills a bunch of people before it turns out they're not people at all. They're aliens too, and, therefore don't matter.

He also gets to take on the National Guard while he's at it.

This comic, almost inevitably, is drawn by Sal Buscema.

Now that Jack Kirby's gone, Marvel clearly feels it's safe to relaunch the Black Panther's strip, carrying on where Don McGregor's run left off, with the conclusion of T'Challa's struggles with the Ku Klux Klan.

I suspect that magic frogs will not feature heavily in this story.

However, those hoping for a healthy dose of Don McGregor's vigorous verbosity are doomed to disappointment, as the tale's written by Ed Hannigan.

Then again, perhaps Ed has the sense to give us what we all want, and decides to emulate Don's writing style.

Labels:

Marvel Lucky Bag

Sunday, 8 December 2019

Forty years ago today - December 1979.

Marvel comics dated, "December 1979." What were they up to? Where were they up to? And why were they up to it?

Hold on to your Santa hats because here's where we find out.

It's an odd tale in which, seeking to escape a pride of lions, Conan decides to spend a night in a haunted house.

Once there, he sees a bunch of other people get killed and then he flees the scene, deciding that discretion's the better part of valour.

Clearly, those who like to see Conan fighting monsters, rather than running away from them, will have to wait until next month.

Galactus sees off the Sphinx by stripping him of his power and then sending him back to Ancient Egypt to live his endless life all over again.

Someone who definitely doesn't have an endless life is Reed Richards who, thanks the Skrulls' ageing ray, is going to be lucky to even make it to the next issue.

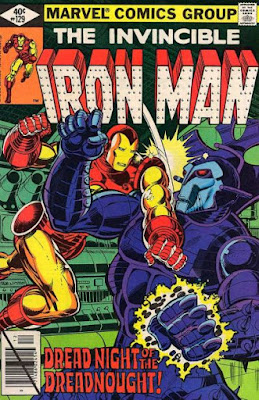

Tony Stark and Nick Fury fall out over ownership of Stark Industries when SHIELD decides to buy a controlling stake in the company, in order to make sure it keeps on churning out the weapons the spy agency loves so much.

Happily, our hero outsmarts Fury - but he still has to face a murderous robot along the way.

Swarm is still impacting upon various students' chances of getting a degree, by trying to kill them.

Fortunately, Spidey's on the scene to sort him out, thanks to having fortified his webbing with a load of insect repellent.

Join Thor in his battle with Red Bull.

Or perhaps I mean with El Toro Rojo, when the Deviant wrestler sets out to make life a misery for an Eternal wrestler, for reasons I can't remember.

Needless to say, no mere wrestler can get the better of a god of thunder, not even one who's a Deviant.

In the streets of Edinburgh, the X-Men finally dispose of Proteus, by doing something or other.

Sadly, I can't recall what it is they actually do.

Captain America spends the whole issue tackling a gang of minor hoodlums, including their leader Big Thunder who's just some bloke.

I suspect this won't go down as one of Cap's greatest adventures.

Tyrannus is still trying to take over the world, thanks to his magic flame in the Andes.

Sadly for him, the Hulk just won't stop hitting things.

The Avengers are having all kinds of trouble with Henry Peter Gyrich but all that has to be put on hold when a monster made of rock crash-lands from space and starts to smash up New York.

But it turns out it's not a monster made of rock at all. It's the Grey Gargoyle who's encased in stone - and, thanks the Avengers, he's now free of that prison and at liberty to cause havoc.

In all honesty, I can't see the Grey Gargoyle being much of a threat to the combined might of the Avengers.

Spidey's out to stop Mysterio and his fraudulent nursing home.

But can he possibly beat a man who can make him think he's losing his mind?

Hold on to your Santa hats because here's where we find out.

It's an odd tale in which, seeking to escape a pride of lions, Conan decides to spend a night in a haunted house.

Once there, he sees a bunch of other people get killed and then he flees the scene, deciding that discretion's the better part of valour.

Clearly, those who like to see Conan fighting monsters, rather than running away from them, will have to wait until next month.

Galactus sees off the Sphinx by stripping him of his power and then sending him back to Ancient Egypt to live his endless life all over again.

Someone who definitely doesn't have an endless life is Reed Richards who, thanks the Skrulls' ageing ray, is going to be lucky to even make it to the next issue.

Tony Stark and Nick Fury fall out over ownership of Stark Industries when SHIELD decides to buy a controlling stake in the company, in order to make sure it keeps on churning out the weapons the spy agency loves so much.

Happily, our hero outsmarts Fury - but he still has to face a murderous robot along the way.

Swarm is still impacting upon various students' chances of getting a degree, by trying to kill them.

Fortunately, Spidey's on the scene to sort him out, thanks to having fortified his webbing with a load of insect repellent.

Join Thor in his battle with Red Bull.

Or perhaps I mean with El Toro Rojo, when the Deviant wrestler sets out to make life a misery for an Eternal wrestler, for reasons I can't remember.

Needless to say, no mere wrestler can get the better of a god of thunder, not even one who's a Deviant.

In the streets of Edinburgh, the X-Men finally dispose of Proteus, by doing something or other.

Sadly, I can't recall what it is they actually do.

Captain America spends the whole issue tackling a gang of minor hoodlums, including their leader Big Thunder who's just some bloke.

I suspect this won't go down as one of Cap's greatest adventures.

Tyrannus is still trying to take over the world, thanks to his magic flame in the Andes.

Sadly for him, the Hulk just won't stop hitting things.

The Avengers are having all kinds of trouble with Henry Peter Gyrich but all that has to be put on hold when a monster made of rock crash-lands from space and starts to smash up New York.

But it turns out it's not a monster made of rock at all. It's the Grey Gargoyle who's encased in stone - and, thanks the Avengers, he's now free of that prison and at liberty to cause havoc.

In all honesty, I can't see the Grey Gargoyle being much of a threat to the combined might of the Avengers.

Spidey's out to stop Mysterio and his fraudulent nursing home.

But can he possibly beat a man who can make him think he's losing his mind?

Labels:

This month in history

Thursday, 5 December 2019

December 5th, 1979 - Marvel UK, 40 years ago this week.

Have you ever felt like you don't need no education?

I know I have.

And that's why the seven days leading up to this date in 1979 were such important ones for me because that's when Pink Floyd's album The Wall was released.

But, of course, we'd already had a taste of it, thanks to the single Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2 having been released in advance and, this very week, it was at Number Two on the UK singles chart, being temporarily held off the top spot by the Police's Walking on the Moon. Perhaps Sting and friends should have called it Walking on the Dark Side of the Moon and then they might have been able to hold the Floyd off permanently.

Speaking of albums, over on the LP chart, the top spot this week was snatched by Rod Stewart who dislodged ABBA's Greatest Hits Vol2, thanks to his own Greatest Hits package.

But it wasn't all good news when it came to the music business because this was also the week in which eleven fans were killed during a crush before The Who's concert at the Riverfront Coliseum in Cincinnati.

All I know of this month's Hulk tale is Bruce Banner goes off to Switzerland, hoping a local scientist can help him with his problem.

I've no doubt at all that that man won't be able to help him with his problem. In fact, I've no doubt he'll simply make it worse.

But I do know we've got a reprint of issue #100 of The X-Men, the one in which the original team fight the new team - until it turns out it's not the original team. It's just a bunch of robots!

In the Dr Strange tale, Clea's being held hostage by Lectra who's using her as leverage to get Strangey to help her find her own mad sister Phaydra.

BaronTagge and his sister are in this issue, so it would appear Darth Vader's not bumped them off yet.

The Guardians of the Galaxy are still battling the Reavers of Arcturus, Deathlok's up against the War-Wolf who would appear to be another cyborg, and The Watcher tells us of a man who decides to take a Martian beauty serum which, I think, makes him look like a Martian.

But easily most significantly, this is the issue in which the mystery of Star-Hawk's identity's finally resolved.

I wish I could remember what that resolution is.

Having said that, isn't the whole point of Star-Hawk that he's a mystery? If his mystery's resolved, doesn't he lose all interest, from the reader's point of view?

The Hulk and Machine Man finally stop fighting each other, for long enough to deal with their true enemy. Who that is, I can't remember but I'm pretty sure he has something to do with The Corporation.

Ant-Man and the Wasp are still stuck at the size of bugs and have now been kidnapped by a robot who wants to give himself the powers of insects.

We're still getting the origins of the Black Knight and Silver Surfer.

And, finally, the Defenders finish off their battle with the Cobalt Man who polishes off Egghead for them.

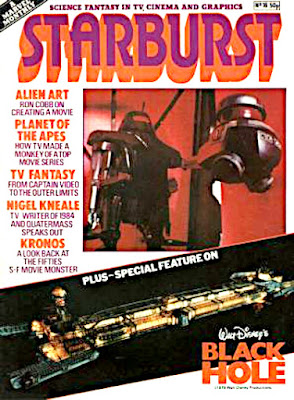

The UK's top sci-fi mag takes a look at The Black Hole, a film I've still, to this day, never seen, even though it's on TV every Christmas. One of these days, I'll have to get round to watching it.

More importantly to me, this issue, Nigel Kneale speaks out. About what, I don't know but I am sure it'll involve everyone's favourite alien-thwarting rocket scientist.

And probably Doctor Who. I've never seen a Nigel Kneale print interview in which the subject of Doctor Who doesn't turn up.

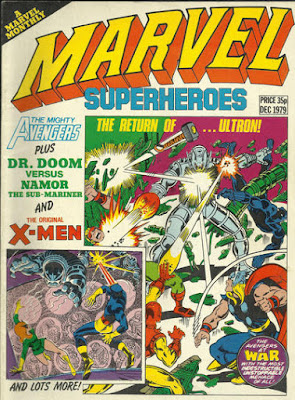

What's this? The Avengers vs Ultron? Dr Doom vs the Sub-Mariner, and the X-Men vs Computo? What more could anyone demand of a comic?

I suppose I could demand it tells me who Computo is, as I've never heard of him/her/it. Regardless, I'm sure Computo's a major threat to humanity.

More urgently, Ultron's happily building a wife for himself - and Hank Pym's helping him!

The Doctor's still having trouble with the Iron Legion, we get a text story based on the William Hartnell adventure The Aztecs, more from War of the Worlds, a feature about the Peter Cushing Dalek movies, and something called The Final Quest which seems to be a tale involving the Sontarans.

Our hero's concluding his tale Beyond the Black River. Beyond that, I can say nothing of this issue other than that it's drawn by John Buscema and Tony DeZuniga.

In the wake of Aunt May's, "death," Peter Parker's at her nursing home and failing to spot who the nursing home manager is, despite him being one of his oldest foes.

We also get Daredevil, Godzilla, the Fantastic Four, Thor and Iron Man in this issue, although I can shed no light on what they're up to.

I know I have.

And that's why the seven days leading up to this date in 1979 were such important ones for me because that's when Pink Floyd's album The Wall was released.

But, of course, we'd already had a taste of it, thanks to the single Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2 having been released in advance and, this very week, it was at Number Two on the UK singles chart, being temporarily held off the top spot by the Police's Walking on the Moon. Perhaps Sting and friends should have called it Walking on the Dark Side of the Moon and then they might have been able to hold the Floyd off permanently.

Speaking of albums, over on the LP chart, the top spot this week was snatched by Rod Stewart who dislodged ABBA's Greatest Hits Vol2, thanks to his own Greatest Hits package.

But it wasn't all good news when it came to the music business because this was also the week in which eleven fans were killed during a crush before The Who's concert at the Riverfront Coliseum in Cincinnati.

All I know of this month's Hulk tale is Bruce Banner goes off to Switzerland, hoping a local scientist can help him with his problem.

I've no doubt at all that that man won't be able to help him with his problem. In fact, I've no doubt he'll simply make it worse.

But I do know we've got a reprint of issue #100 of The X-Men, the one in which the original team fight the new team - until it turns out it's not the original team. It's just a bunch of robots!

In the Dr Strange tale, Clea's being held hostage by Lectra who's using her as leverage to get Strangey to help her find her own mad sister Phaydra.

BaronTagge and his sister are in this issue, so it would appear Darth Vader's not bumped them off yet.

The Guardians of the Galaxy are still battling the Reavers of Arcturus, Deathlok's up against the War-Wolf who would appear to be another cyborg, and The Watcher tells us of a man who decides to take a Martian beauty serum which, I think, makes him look like a Martian.

But easily most significantly, this is the issue in which the mystery of Star-Hawk's identity's finally resolved.

I wish I could remember what that resolution is.

Having said that, isn't the whole point of Star-Hawk that he's a mystery? If his mystery's resolved, doesn't he lose all interest, from the reader's point of view?

The Hulk and Machine Man finally stop fighting each other, for long enough to deal with their true enemy. Who that is, I can't remember but I'm pretty sure he has something to do with The Corporation.

Ant-Man and the Wasp are still stuck at the size of bugs and have now been kidnapped by a robot who wants to give himself the powers of insects.

We're still getting the origins of the Black Knight and Silver Surfer.

And, finally, the Defenders finish off their battle with the Cobalt Man who polishes off Egghead for them.

The UK's top sci-fi mag takes a look at The Black Hole, a film I've still, to this day, never seen, even though it's on TV every Christmas. One of these days, I'll have to get round to watching it.

More importantly to me, this issue, Nigel Kneale speaks out. About what, I don't know but I am sure it'll involve everyone's favourite alien-thwarting rocket scientist.

And probably Doctor Who. I've never seen a Nigel Kneale print interview in which the subject of Doctor Who doesn't turn up.

What's this? The Avengers vs Ultron? Dr Doom vs the Sub-Mariner, and the X-Men vs Computo? What more could anyone demand of a comic?

I suppose I could demand it tells me who Computo is, as I've never heard of him/her/it. Regardless, I'm sure Computo's a major threat to humanity.

More urgently, Ultron's happily building a wife for himself - and Hank Pym's helping him!

The Doctor's still having trouble with the Iron Legion, we get a text story based on the William Hartnell adventure The Aztecs, more from War of the Worlds, a feature about the Peter Cushing Dalek movies, and something called The Final Quest which seems to be a tale involving the Sontarans.

Our hero's concluding his tale Beyond the Black River. Beyond that, I can say nothing of this issue other than that it's drawn by John Buscema and Tony DeZuniga.

In the wake of Aunt May's, "death," Peter Parker's at her nursing home and failing to spot who the nursing home manager is, despite him being one of his oldest foes.

We also get Daredevil, Godzilla, the Fantastic Four, Thor and Iron Man in this issue, although I can shed no light on what they're up to.

Labels:

Marvel UK 40 years ago this week

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)