In its latest gift to the internet, mere days ago Steve Does Comics somehow managed to demonstrate that Conan the Barbarian is Scottish.

No doubt he comes from Cumbernauld and began his descent into barbaric fury whilst trying to navigate that town's legendarily inconvenient centre. The glorious perverseness of that place means Cumbernauld has always featured high in my affections even though I've never been there.

Likewise high in my affections even though I've never experienced it is Marvel UK's Savage Sword of Conan #1.

In their time, Marvel UK launched at least two comics called Savage Sword of Conan, one of which was a later, magazine-sized, monthly of which I had one issue.

The earlier, weekly, comic was launched in 1975 and, in a tragedy worthy of Shakespeare himself, I never had a single copy.

I did however see it advertised on TV and saw Stan Lee plugging it - possibly on ITV's classic kids' show Magpie.

It was thanks to that very interview that I discovered that Conan is pronounced Coe-nan and not Connan. It was as big a shock to the system as discovering that, "Sub-Mariner," isn't pronounced Sub-Mareener. Who says television can't be educational?

Sadly, despite my desire to own it. I never had issue #1 and had to wait many a moon before finally reading its fateful featured tale, in The Essential Conan which I then threw away to make room for other objects.

Happily, that book is now selling for over £90 on Amazon. And so the business genius that has made me the man I am today, once more showed its fearful face.

Tuesday, 29 January 2013

Saturday, 26 January 2013

Marvel's Black and White mags.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

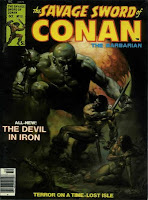

They might have just been comics but, with their painted covers, extra pages, features, articles and lushly monochrome artwork, they seemed so much more grown-up than any comic had a right to be.

I had ten of them, which by an incredible coincidence just happen to be the ten pictured to the left of this very post.

As you may have guessed The Savage Sword of Conan made a big impression on me and I made sure to get any issue of it I laid my eyes on. If any comic strip was ever suited to such a format, it had to be the adventures of the Hibernian hackmeister.

As mentioned elsewhere on this blog, John Buscema and Alfredo Alcala's adaptation of Iron Shadows in the Moon was a classic of the genre, with a level of illustration that couldn't fail to blow the mind of any unsuspecting ten year old who might encounter it for the first time.

But the duo's The Citadel at the Center of Time and Alex Nino's The Lurkers Below ran it close when it came to Steve appeal.

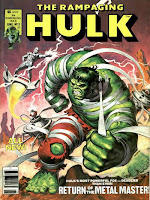

I got all three issues that I owned of The Rampaging Hulk during one summer holiday, and its tales of the Hulk's wilderness years between the cancellation of his original comic and his reappearance in Tales To Astonish always tickled my fancy at the time, even if the stories were lumbered with surely the worst race of evil aliens ever inflicted upon comicdom, and the backup strip Bloodstone meant nothing to me.

Of the ten mags I had, Monsters Unleashed #11 was probably the weakest, featuring a bandwagon-jumping exorcist and the adventures of a Komodo dragon.

Meanwhile, even though it could only be viewed as an emergency issue - cobbled together from unfinished tales, Jan of the Jungle and a Ka-Zar reprint - with its Neal Adams cover, Savage Tales #6 always grabbed me mightily.

The black and white mags were a venture by Marvel into a more adult market, one that ultimately failed in not just its commercial aim but also its artistic one, in that they were barely more adult than the full-colour monthlies. What nudity there was could mostly only be labelled, "coy," strategically placed hair often being the order of the day. Genuine emotional and intellectual depth was mostly absent. And it would appear, from the editorials that accompanied the Savage Tales and Monsters Unleashed issues, that actually scraping together enough material to fill them in time for the deadline was a major problem.

The Savage Sword of Conan, of course, was a massive success, running for a zillion years before Marvel finally went mad and relinquished their rights to the character. Marvel's other black and white mags mostly struggled to make it into double figures before the plug was pulled. Could they have succeeded if they had indeed been more adult, or did the lack of colour mean they were always doomed to struggle in an American market that took multi-hued heroes for granted? I don't have a clue but I do know that, whatever their failings, they were fun while they lasted.

Labels:

Marvel Black and White Mags

Thursday, 24 January 2013

Sheffield's Most Wanted. Part 13: Vampire Tales #10.

"Steve!" people demand. "Why did you stop doing Sheffield's Most Wanted? Was it because you feared such excitement might blow people's minds and leave them as barely more than vegetables?"

No, I tell them. It was because I'm half-senile and had totally forgotten the feature ever existed.

Well, that's all changed now because perusing my old posts has brought it back into my consciousness as never before.

And that can only mean one thing.

It's time for me to ramble on about yet another comic I never owned as a kid but always wanted to.

As a child, I only knew of Vampire Tales #10 from monochrome ads in such mags as Savage Sword of Conan and Monsters Unleashed but that was enough to grab me.

Such was the allure of those adverts that, using the most sophisticated image-processing software known to man, I've removed the colour from that cover just to remind myself of it as I know it best.

I'm not sure I knew back then who Morbius was - I almost certainly saw the ads before I'd read his debut reprinted in Spider-Man Comics Weekly - but, having experienced Marvel's other black and white titles, and one issue of Vampirella, I was well up for some magazine format vampirism.

I'm not sure I knew back then who Morbius was - I almost certainly saw the ads before I'd read his debut reprinted in Spider-Man Comics Weekly - but, having experienced Marvel's other black and white titles, and one issue of Vampirella, I was well up for some magazine format vampirism.

Let's face it, who could resist a blurb like, "Even Morbius cannot survive the Plague of Blood!"?

And who could resist that cover, which the GCD informs me is by Richard Hescox, an artist of whom I must admit I know nothing.

So, there you have it; a character of whom I knew nothing, painted by an artist of whom I knew nothing, in a magazine of which I knew nothing. If that doesn't prove the power of mystery, then what could?

No, I tell them. It was because I'm half-senile and had totally forgotten the feature ever existed.

Well, that's all changed now because perusing my old posts has brought it back into my consciousness as never before.

And that can only mean one thing.

It's time for me to ramble on about yet another comic I never owned as a kid but always wanted to.

As a child, I only knew of Vampire Tales #10 from monochrome ads in such mags as Savage Sword of Conan and Monsters Unleashed but that was enough to grab me.

Such was the allure of those adverts that, using the most sophisticated image-processing software known to man, I've removed the colour from that cover just to remind myself of it as I know it best.

I'm not sure I knew back then who Morbius was - I almost certainly saw the ads before I'd read his debut reprinted in Spider-Man Comics Weekly - but, having experienced Marvel's other black and white titles, and one issue of Vampirella, I was well up for some magazine format vampirism.

I'm not sure I knew back then who Morbius was - I almost certainly saw the ads before I'd read his debut reprinted in Spider-Man Comics Weekly - but, having experienced Marvel's other black and white titles, and one issue of Vampirella, I was well up for some magazine format vampirism.Let's face it, who could resist a blurb like, "Even Morbius cannot survive the Plague of Blood!"?

And who could resist that cover, which the GCD informs me is by Richard Hescox, an artist of whom I must admit I know nothing.

So, there you have it; a character of whom I knew nothing, painted by an artist of whom I knew nothing, in a magazine of which I knew nothing. If that doesn't prove the power of mystery, then what could?

Labels:

Morbius,

Sheffield's Most Wanted

Wednesday, 16 January 2013

Killraven - Only The Computer Shows Me Any Respect. Amazing Adventures #32.

As I stand in the middle of Argos - studying its catalogue, for high-end tripods to support my state-of-the art single megapixel camera - people often say to me, "Steve, I know you're a very busy man and don't like to be interrupted by those you view as beneath your contempt but what's your favourite ever literary depiction of tripods for sinister effect?"

I of course reply, "Well there was John Christopher's The Tripods, famously reimagined by the BBC as a show about wine production in Southern France but, when it comes to three-legged terror, I have to go for War of the Worlds, HG Wells' reminder of the dangers of getting too big for your boots."

"But Steve," they say, "you're too big for your boots and it doesn't seem to have done you any harm. After all, here you are in Argos, where only the top people shop."

"Pshaw!" I declare. "My toes are so tough that, when footwear proves too small to contain them, they merely burst out of my shoes, giving me the stylish look you see before you today."

Not only that but, as I roam the corridors of Sheffield's hi-tech virtual reality enormo-dome, otherwise known as the Flat Street Odeon, people often say to me, "Steve, pretty impressive, isn't it? But did you know this used to be the Fiesta Club, once the haunt of stars like Bobby Knutt and the Black Abbots but not necessarily those actual stars?"

All such talk of tripods and virtual reality inevitably forces my mind onto the subject of what has always been my favourite ever Killraven story, Amazing Adventures #32, which is low on tripods but high on virtual shenanigans.

Doing their usual meanderings, Killraven and his band of freemen come across an abandoned virtual reality entertainment complex that gives your fantasies - and nightmares - physical form.

Needless to say, it's not long before they're all philosophising and getting into trouble.

Thanks to Old Skull and his fantasies, Killraven finds himself up against a fire-breathing dragon; a conflict which forms the issue's "A" plot.

But the tale's most memorable sequence is its "B" plot, a flashback to Hawk's youth which finds him arguing with his father and leads to the appearance of Hodiah Twist, a Sherlock Holmes figure so self-assured he refuses to believe the Hound of the Baskervilles is real even when it's killing him.

In a lot of ways, the sequence now seems spiritually hackneyed. Hawk is an American Indian and, this being a 1970s Marvel comic, that means he has to be a bitter and sullen man, brooding on broken treaties and the grimness of the Reservation.

Still, if the theme is over-familiar in a 1970s comic book, the flashback's sudden diversion into an Arthur Conan Doyle parody makes it oddly charming and memorable, the English moors allowing a drastic change in the strip's visual palette.

Don McGregor's script is as verbose as ever but doesn't seem as intrusive or deadening as it sometimes can - possibly because there's very little plot for his words to get in the way of, allowing them plenty of space to expand into and to make it clear that he sees a comic book as a legitimate form of short story writing.

But, ultimately, whatever its literary pretensions, it's a comic, and a comic's nothing without pictures. As always Craig Russell plays a blinder. Given a chance to fling in the psychedelic, the archaic, the futuristic, the industrial and the cute, he seems to be having a ball drawing it all.

It's not a comic I love as much as I did when I was young - frankly, there'd be something wrong me me if I did; I must confess to having been quite obsessed with it at the time - but it'd still go on my list of 1970s issues you have to have read in order for your Bronze Age comics education to be complete.

I of course reply, "Well there was John Christopher's The Tripods, famously reimagined by the BBC as a show about wine production in Southern France but, when it comes to three-legged terror, I have to go for War of the Worlds, HG Wells' reminder of the dangers of getting too big for your boots."

"But Steve," they say, "you're too big for your boots and it doesn't seem to have done you any harm. After all, here you are in Argos, where only the top people shop."

"Pshaw!" I declare. "My toes are so tough that, when footwear proves too small to contain them, they merely burst out of my shoes, giving me the stylish look you see before you today."

Not only that but, as I roam the corridors of Sheffield's hi-tech virtual reality enormo-dome, otherwise known as the Flat Street Odeon, people often say to me, "Steve, pretty impressive, isn't it? But did you know this used to be the Fiesta Club, once the haunt of stars like Bobby Knutt and the Black Abbots but not necessarily those actual stars?"

All such talk of tripods and virtual reality inevitably forces my mind onto the subject of what has always been my favourite ever Killraven story, Amazing Adventures #32, which is low on tripods but high on virtual shenanigans.

Doing their usual meanderings, Killraven and his band of freemen come across an abandoned virtual reality entertainment complex that gives your fantasies - and nightmares - physical form.

Needless to say, it's not long before they're all philosophising and getting into trouble.

Thanks to Old Skull and his fantasies, Killraven finds himself up against a fire-breathing dragon; a conflict which forms the issue's "A" plot.

But the tale's most memorable sequence is its "B" plot, a flashback to Hawk's youth which finds him arguing with his father and leads to the appearance of Hodiah Twist, a Sherlock Holmes figure so self-assured he refuses to believe the Hound of the Baskervilles is real even when it's killing him.

In a lot of ways, the sequence now seems spiritually hackneyed. Hawk is an American Indian and, this being a 1970s Marvel comic, that means he has to be a bitter and sullen man, brooding on broken treaties and the grimness of the Reservation.

Still, if the theme is over-familiar in a 1970s comic book, the flashback's sudden diversion into an Arthur Conan Doyle parody makes it oddly charming and memorable, the English moors allowing a drastic change in the strip's visual palette.

Don McGregor's script is as verbose as ever but doesn't seem as intrusive or deadening as it sometimes can - possibly because there's very little plot for his words to get in the way of, allowing them plenty of space to expand into and to make it clear that he sees a comic book as a legitimate form of short story writing.

But, ultimately, whatever its literary pretensions, it's a comic, and a comic's nothing without pictures. As always Craig Russell plays a blinder. Given a chance to fling in the psychedelic, the archaic, the futuristic, the industrial and the cute, he seems to be having a ball drawing it all.

It's not a comic I love as much as I did when I was young - frankly, there'd be something wrong me me if I did; I must confess to having been quite obsessed with it at the time - but it'd still go on my list of 1970s issues you have to have read in order for your Bronze Age comics education to be complete.

Labels:

Amazing Adventures,

Killraven

Thursday, 10 January 2013

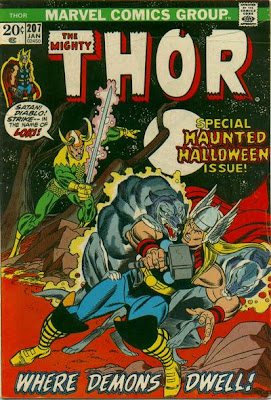

Forty Years ago this month - January 1973.

January Jones was in X-Men First Class.

The X-Men is a comic.

This is Steve Does Comics.

And it's currently January.

That can only mean one thing.

It's time for me to do my Leonard Rossiter impression: "Ooh no, Miss Jones. Get down, Vienna. Look at that - reflexes like a coiled spring. The permissive society, it doesn't exist. I should know - I've looked hard enough for it."

Almost as impressively, it also means it's time for me to look at what our favourite Marvel heroes were up to in January of exactly forty years ago.

The Grim Reaper's back and causing yet more trouble for our heroes.

Despite what the cover tells us, I'm pretty sure he hasn't been drinking Hank Pym's size-changing formula though.

The Smasher is anything but smashing as politics enters the world of Spider-Man.

I don't think I've ever read this one.

Nor have I ever heard of the Viper.

They don't call me "Mr Knowledgeable" for nothing.

It might be The Shadow of the Vulture on the cover but that's not what we get inside, as the loss of Barry Smith's artwork in the mail forces Marvel to reprint issue #1.

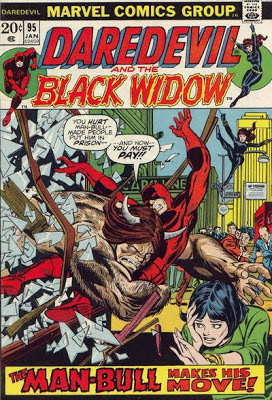

Hooray! Man-Bull's still throwing his weight around.

I do genuinely believe there was no such thing as a bad Hulk tale from the early 1970s - and issue #159 does nothing to dissuade me from that notion, as the Abomination's back and a little confused about what time it is.

Apparently, this cover's by Jim Steranko though you have to look fairly hard at it to notice.

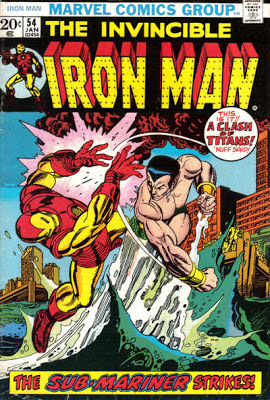

Go on Subby! Smack him one!

Is this the one where we get to see Jean Thomas dressed as Supergirl?

Possibly more importantly, is this the one where Loki falls off a cliff?

The X-Men is a comic.

This is Steve Does Comics.

And it's currently January.

That can only mean one thing.

It's time for me to do my Leonard Rossiter impression: "Ooh no, Miss Jones. Get down, Vienna. Look at that - reflexes like a coiled spring. The permissive society, it doesn't exist. I should know - I've looked hard enough for it."

Almost as impressively, it also means it's time for me to look at what our favourite Marvel heroes were up to in January of exactly forty years ago.

The Grim Reaper's back and causing yet more trouble for our heroes.

Despite what the cover tells us, I'm pretty sure he hasn't been drinking Hank Pym's size-changing formula though.

The Smasher is anything but smashing as politics enters the world of Spider-Man.

I don't think I've ever read this one.

Nor have I ever heard of the Viper.

They don't call me "Mr Knowledgeable" for nothing.

It might be The Shadow of the Vulture on the cover but that's not what we get inside, as the loss of Barry Smith's artwork in the mail forces Marvel to reprint issue #1.

Hooray! Man-Bull's still throwing his weight around.

I do genuinely believe there was no such thing as a bad Hulk tale from the early 1970s - and issue #159 does nothing to dissuade me from that notion, as the Abomination's back and a little confused about what time it is.

Apparently, this cover's by Jim Steranko though you have to look fairly hard at it to notice.

Go on Subby! Smack him one!

Is this the one where we get to see Jean Thomas dressed as Supergirl?

Possibly more importantly, is this the one where Loki falls off a cliff?

Labels:

This month in history

Monday, 7 January 2013

Jim Starlin's All-Time Top Ten Mighty World of Marvel Covers.

As we all know, in the 1970s, there was no one quite like Jim Starlin when it came to Cosmic-ing up comic books. It seemed like, given half-a-chance, he could even have turned the adventures of Roy Race into an intergalactic epic.

But the man they call Judo Jim had a more important part to play in comic book history than even that.

That's because, for several months, he was the main cover artist on Marvel UK's flagship title Mighty World of Marvel. This was before his cosmic heyday but, even in the early 1970s, the seeds of his future greatness were there for everyone to see.

Therefore, Steve Does Comics gives its not in the slightest bit definitive list of Jim Starlin's ten greatest Mighty World of Marvel covers.

Remember, this list is compiled without the aid of insight, taste or expert knowledge and makes no claims to being at all right in its opinions.

But the man they call Judo Jim had a more important part to play in comic book history than even that.

That's because, for several months, he was the main cover artist on Marvel UK's flagship title Mighty World of Marvel. This was before his cosmic heyday but, even in the early 1970s, the seeds of his future greatness were there for everyone to see.

Therefore, Steve Does Comics gives its not in the slightest bit definitive list of Jim Starlin's ten greatest Mighty World of Marvel covers.

Remember, this list is compiled without the aid of insight, taste or expert knowledge and makes no claims to being at all right in its opinions.

10.

Spidey comes up against a surprisingly stylishly dressed Lizard, while the floating heads of the Fantastic Four and the Hulk look suitably startled.

9.

That bounder Dr Doom's up to no good - both of him.

Daredevil's so sickened by it all that he can't resist throwing away his stick.

He'll regret that later. You never known when you might need a stick.

8.

It's Doom vs Spidey.

Do my razor-sharp senses spot a helping hand from Jazzy John Romita on the figure of Spider-Man?

7.

The Hulk gets zapped.

6.

It's brain vs brawn, as the Leader causes his usual mischief.

5.

How can the FF possibly hope to defeat both the Sub-Mariner and Dr Doom?

I reckon they'll be fine as long as no one tries to launch the Baxter Building into outer space.

4.

This was the first issue of Mighty World of Marvel I ever read - and what a way to start, as Spidey battles the FF.

3.

The FF vs the Hulk.

Daredevil's throwing his stick away again.

Will he never learn?

2.

If the sight of the Hulk smashing through a wall doesn't make you want to buy a comic, then what would?

1.

Spidey might have quit the comic but a new hero's introduced to readers, as Daredevil makes his entrance.

All scans from the Grand Comics Database.

Labels:

Mighty World of Marvel,

Top Tens

Saturday, 5 January 2013

The Amazing Spider-Man 50th Anniversary Edition Vintage Annual.

From the moment I first discovered the existence of Panini's Amazing Spider-Man 50th Anniversary Edition Vintage Annual, I knew I had no good reason for buying it. After all, thanks to the Marvel Essentials, I already have copies of every tale in it.

Did that mean I didn't want it?

Of course it didn't. Just as I must buy chocolate even though I know it's bad for me, I knew at once that I craved this book.

Why?

Because it was nearly Christmas - and I knew I would've loved to have got it for Christmas when I was ten.

Sadly, the RRP of £12.99 for just under a hundred and thirty pages put it beyond the reach of one as tight-fisted as I. But, like any good super-villain, I'm a man who knows how to bide his time and, happily, as I expected, with Christmas gone, it's now available for just £4.55 from Amazon, and with free postage.

Suddenly my Scroogelicious tendencies were being appealed to as never before and, like the Green Goblin, I knew I must strike.

How much do I love this book?

Bigly.

If ever I needed confirmation that I am indeed the centre of the universe, this tome confirms it for me because it features only stories with a special significance for me.

The first appearance of the Sinister Six was the first Spider-Man tale I ever read.

Amazing Spider-Man #1 was the first Spider-Man story I ever read in The Mighty World of Marvel.

The Lizard has always been my favourite Spider-Man villain and, so his first appearance has always grabbed me.

And I first read Spider-Man's Amazing Fantasy origin in Origins of Marvel Comics, one Christmas morning.

Not only that but it has the Secrets of Spider-Man feature that showed up in Fleetway's legendary 1972/73 Marvel Annual - the one that includes the image of our hero lifting a giant barbell as Thor, the Hulk and the Thing watch on.

It even has that tongue-in-cheek feature on how Steve Ditko and Stan Lee create an issue of Spider-Man, the one that shows Spidey flying past the Statue of Liberty, on a rocket. For many years, this feature contained the sum total of my knowledge of how a comic is created.

It also features a full-page cutaway spread of Peter Parker's house, a full-page spread of Flash Thompson flexing his muscles for his adoring high school fans and full-page spread of J Jonah Jameson haranguing Betty Brant. Maybe I have a faulty memory but I don't remember ever seeing any of these three illustrations before.

It also has a villains gallery, featuring the portraits of Spidey foes that were used in one of the text features of that Fleetway Annual.

But, for me, perhaps the most interesting thing is seeing some of these tales and features in colour for the first time. Happily, the colouring's old style rather than that new-fangled method that over-complicates and half-obscures the linework - although there's a more modern style to some of the backgrounds, making them contrast nicely with the simpler figures in the foreground.

Another plus is the chance to see Ditko's full-page splashes from the Sinister Six tale in a much bigger format than we're used to.

The book's main gimmick is that the pages have been artificially aged, with tanning around the edges, fake water rippling and even creases. Really, this shouldn't add to the book's appeal but, because I'm a total mug, it does.

Fans of Stan Lee will be pleased to see we get an intro from the man himself.

Any quibbles are minor. Given that all the stories and features within are by Steve Ditko, it seems strange that none of the illustrations on the front cover are by him. Also, I know a hundred and thirty pages is a decent count for a modern annual but, given that it's a fiftieth anniversary special - and therefore unique - even more pages would have been appreciated. I still recall those doorstop thick annuals from my childhood and dream we might see their like again someday.

So there you have it - a book that's inherently redundant to me but that already feels like a treasured possession.

Oh but if only Panini had thought of doing the same for the Fantastic Four, the Hulk and Thor's 50th Anniversaries...

Did that mean I didn't want it?

Of course it didn't. Just as I must buy chocolate even though I know it's bad for me, I knew at once that I craved this book.

Why?

Because it was nearly Christmas - and I knew I would've loved to have got it for Christmas when I was ten.

Sadly, the RRP of £12.99 for just under a hundred and thirty pages put it beyond the reach of one as tight-fisted as I. But, like any good super-villain, I'm a man who knows how to bide his time and, happily, as I expected, with Christmas gone, it's now available for just £4.55 from Amazon, and with free postage.

Suddenly my Scroogelicious tendencies were being appealed to as never before and, like the Green Goblin, I knew I must strike.

How much do I love this book?

Bigly.

If ever I needed confirmation that I am indeed the centre of the universe, this tome confirms it for me because it features only stories with a special significance for me.

The first appearance of the Sinister Six was the first Spider-Man tale I ever read.

Amazing Spider-Man #1 was the first Spider-Man story I ever read in The Mighty World of Marvel.

The Lizard has always been my favourite Spider-Man villain and, so his first appearance has always grabbed me.

And I first read Spider-Man's Amazing Fantasy origin in Origins of Marvel Comics, one Christmas morning.

Not only that but it has the Secrets of Spider-Man feature that showed up in Fleetway's legendary 1972/73 Marvel Annual - the one that includes the image of our hero lifting a giant barbell as Thor, the Hulk and the Thing watch on.

It even has that tongue-in-cheek feature on how Steve Ditko and Stan Lee create an issue of Spider-Man, the one that shows Spidey flying past the Statue of Liberty, on a rocket. For many years, this feature contained the sum total of my knowledge of how a comic is created.

It also features a full-page cutaway spread of Peter Parker's house, a full-page spread of Flash Thompson flexing his muscles for his adoring high school fans and full-page spread of J Jonah Jameson haranguing Betty Brant. Maybe I have a faulty memory but I don't remember ever seeing any of these three illustrations before.

It also has a villains gallery, featuring the portraits of Spidey foes that were used in one of the text features of that Fleetway Annual.

But, for me, perhaps the most interesting thing is seeing some of these tales and features in colour for the first time. Happily, the colouring's old style rather than that new-fangled method that over-complicates and half-obscures the linework - although there's a more modern style to some of the backgrounds, making them contrast nicely with the simpler figures in the foreground.

Another plus is the chance to see Ditko's full-page splashes from the Sinister Six tale in a much bigger format than we're used to.

The book's main gimmick is that the pages have been artificially aged, with tanning around the edges, fake water rippling and even creases. Really, this shouldn't add to the book's appeal but, because I'm a total mug, it does.

Fans of Stan Lee will be pleased to see we get an intro from the man himself.

Any quibbles are minor. Given that all the stories and features within are by Steve Ditko, it seems strange that none of the illustrations on the front cover are by him. Also, I know a hundred and thirty pages is a decent count for a modern annual but, given that it's a fiftieth anniversary special - and therefore unique - even more pages would have been appreciated. I still recall those doorstop thick annuals from my childhood and dream we might see their like again someday.

So there you have it - a book that's inherently redundant to me but that already feels like a treasured possession.

Oh but if only Panini had thought of doing the same for the Fantastic Four, the Hulk and Thor's 50th Anniversaries...

Labels:

Annuals,

Marvel Annual,

Spider-Man

Thursday, 3 January 2013

January 1963 - Fifty Years Ago Today.

January brings with it a new year. And that can only mean one thing.

It's time to take a look at what our favourite Marvel heroes - and Ant-Man - were up to exactly fifty years ago.

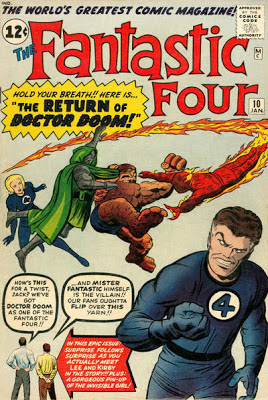

Is this the one where Dr Doom swaps bodies with Reed Richards?

More importantly, is it the one where he has the FF followed around all day long by floating Mr Blobby clones? What exactly was the reason for that? My fading memory furnishes me with no explanations.

Hooray! One of my favourite villains - and close personal role models - makes his debut, as Tyrannus shows us all just how to run a subterranean kingdom.

So impressed have I always been by this tale, that you can find a review of it, right here.

That rarest of things, a Thor cover where the god of thunder isn't declaring himself to be doomed without even putting up a fight.

Good to see Odin being as useless as ever in a crisis, though.

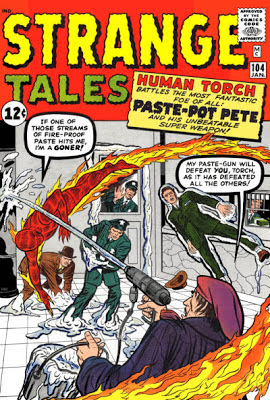

"The most fantastic foe of all!" Stan declares on the cover. "And his unbeatable super-weapon!"

That's right. It's that epic bundle of awe the world knows as Paste-Pot Pete.

Ant-Man may rarely inspire some of us but, this month, he does at least get to feature in what has to be one of the greatest covers in comic book history.

Why didn't the Scarlet Beetle go on to fight every hero in Marveldom over the years? Clearly there's no justice in the world.

If only he'd had the sense to wear underpants, like Fin Fang Foom, I have no doubt he'd have gone down in the annals of greatness.

It's time to take a look at what our favourite Marvel heroes - and Ant-Man - were up to exactly fifty years ago.

Is this the one where Dr Doom swaps bodies with Reed Richards?

More importantly, is it the one where he has the FF followed around all day long by floating Mr Blobby clones? What exactly was the reason for that? My fading memory furnishes me with no explanations.

Hooray! One of my favourite villains - and close personal role models - makes his debut, as Tyrannus shows us all just how to run a subterranean kingdom.

So impressed have I always been by this tale, that you can find a review of it, right here.

That rarest of things, a Thor cover where the god of thunder isn't declaring himself to be doomed without even putting up a fight.

Good to see Odin being as useless as ever in a crisis, though.

"The most fantastic foe of all!" Stan declares on the cover. "And his unbeatable super-weapon!"

That's right. It's that epic bundle of awe the world knows as Paste-Pot Pete.

Ant-Man may rarely inspire some of us but, this month, he does at least get to feature in what has to be one of the greatest covers in comic book history.

Why didn't the Scarlet Beetle go on to fight every hero in Marveldom over the years? Clearly there's no justice in the world.

If only he'd had the sense to wear underpants, like Fin Fang Foom, I have no doubt he'd have gone down in the annals of greatness.

Labels:

Fifty years ago today

Tuesday, 1 January 2013

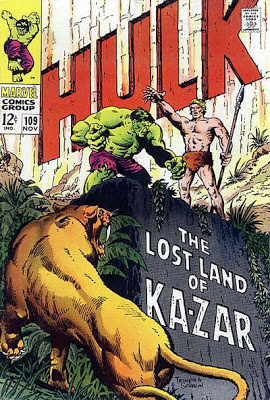

Incredible Hulk #109 - Ka-Zar!

Those of an observant nature will know that Christmas was an exciting time for me.

When I say, "Observant," I mean, "Fixated," and, "Prone to stalking," as only such people would know I spent the Festive Season braving the wilds of Devon.

American visitors to this blog will of course not know the dread reputation Devon has amongst the God-fearing folk of England. What savage terrors I encountered there as I was forced to battle manfully with various wild animals for supremacy.

Needless to say, I was triumphant, managed to get the blanket off the cats on more than one occasion, avoided tripping over a dog and lived to tell the tale.

But who else could have managed such a feat?

Only one man could.

And that man is Ka-Zar: king of the Savage Land.

And so it was that, as I roamed, bare-chested, the fields of Devon, people would often say to me, "Steve, having someone of your fame in our little county's quite an honour but when did you first encounter the loin-clothed loiterer on whom you've clearly based your survival skills?"

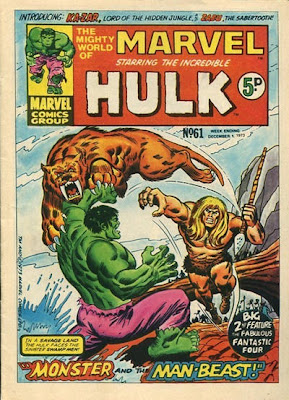

And the truth is it was in Mighty World of Marvel #61.

This is a good thing. Mighty World of Marvel #61 holds a special place in my heart. Not only was it one of the earliest comics I collected but its reprint of Incredible Hulk #109 features one of my fave Hulk tales, as the green skinned stirrer lands in the Savage Land and proceeds to make a nuisance of himself before saving the world from a machine that can make it rain a lot.

First of all, of course, he has to fight Ka-Zar.

Frankly, against such opposition, Ka-Zar's totally outclassed.

When I first read the tale, knowing nothing of the character, it didn't strike me just how outclassed he really is but he and Zabu are soon dispatched by the Hulk and left to the tender mercies of the Swamp Men who're in the mood to set light to them.

Frankly that's the least of their worries because it seems some naughty aliens have planted a doomsday machine in the Savage Land and it's in full swing.

What can even the Hulk do to stop such carnage?

It turns out he can't do anything but Bruce Banner can and Bruce battles to sort things out, as a giant robot stomps the land.

It's not hard to see just what the appeal of the tale is. The mixture of the Hulk, prehistoric creatures, jungles, aliens, Tarzan clones and giant robots is a heady and evocative mix. Not only did the tale introduce me to Ka-Zar and Zabu but it introduced me to the Savage Land itself - and Umbu the giant four-armed alien statue with a killer tuning fork.

Herb Trimpe had been drawing the strip for a few issues when this tale started but, for me, this was the tale where he really arrived, his partnership with John Severin hitting its stride to take the title to heights it had rarely even aspired to before but rarely fell from from that moment on.

Within mere weeks, the Hulk would be in outer space battling a giant mouth in space, Betty Ross would be made of glass, the Leader would be back and the strip would exert a grip on me that, even all this time later, those tales still hold. It's not often you can view an individual issue as pivotal in a strip's history but I reckon The Incredible Hulk #109 is more than worthy of that description.

When I say, "Observant," I mean, "Fixated," and, "Prone to stalking," as only such people would know I spent the Festive Season braving the wilds of Devon.

American visitors to this blog will of course not know the dread reputation Devon has amongst the God-fearing folk of England. What savage terrors I encountered there as I was forced to battle manfully with various wild animals for supremacy.

Needless to say, I was triumphant, managed to get the blanket off the cats on more than one occasion, avoided tripping over a dog and lived to tell the tale.

But who else could have managed such a feat?

Only one man could.

And that man is Ka-Zar: king of the Savage Land.

And so it was that, as I roamed, bare-chested, the fields of Devon, people would often say to me, "Steve, having someone of your fame in our little county's quite an honour but when did you first encounter the loin-clothed loiterer on whom you've clearly based your survival skills?"

And the truth is it was in Mighty World of Marvel #61.

This is a good thing. Mighty World of Marvel #61 holds a special place in my heart. Not only was it one of the earliest comics I collected but its reprint of Incredible Hulk #109 features one of my fave Hulk tales, as the green skinned stirrer lands in the Savage Land and proceeds to make a nuisance of himself before saving the world from a machine that can make it rain a lot.

First of all, of course, he has to fight Ka-Zar.

Frankly, against such opposition, Ka-Zar's totally outclassed.

When I first read the tale, knowing nothing of the character, it didn't strike me just how outclassed he really is but he and Zabu are soon dispatched by the Hulk and left to the tender mercies of the Swamp Men who're in the mood to set light to them.

Frankly that's the least of their worries because it seems some naughty aliens have planted a doomsday machine in the Savage Land and it's in full swing.

What can even the Hulk do to stop such carnage?

It turns out he can't do anything but Bruce Banner can and Bruce battles to sort things out, as a giant robot stomps the land.

It's not hard to see just what the appeal of the tale is. The mixture of the Hulk, prehistoric creatures, jungles, aliens, Tarzan clones and giant robots is a heady and evocative mix. Not only did the tale introduce me to Ka-Zar and Zabu but it introduced me to the Savage Land itself - and Umbu the giant four-armed alien statue with a killer tuning fork.

Herb Trimpe had been drawing the strip for a few issues when this tale started but, for me, this was the tale where he really arrived, his partnership with John Severin hitting its stride to take the title to heights it had rarely even aspired to before but rarely fell from from that moment on.

Within mere weeks, the Hulk would be in outer space battling a giant mouth in space, Betty Ross would be made of glass, the Leader would be back and the strip would exert a grip on me that, even all this time later, those tales still hold. It's not often you can view an individual issue as pivotal in a strip's history but I reckon The Incredible Hulk #109 is more than worthy of that description.

Labels:

Hulk,

Ka-Zar,

Mighty World of Marvel

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

%20040a.jpg)